Weill Cornell Medicine researchers have discovered a mechanism that ovarian tumors use to cripple immune cells and impede their attack – blocking the energy supply T cells depend on. The work, , points toward a promising new immunotherapy approach for ovarian cancer, which is notoriously aggressive and hard to treat.

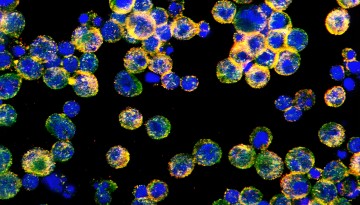

A significant obstacle in treating ovarian cancer is the tumor microenvironment – the complex ecosystem of cells, molecules and blood vessels that shields cancer cells from the immune system. Within this hostile environment, T cells lose their ability to take up lipid (fat) molecules, which are necessary for energy to mount an effective attack.

“T cells rely on lipids as fuel, burning them in their mitochondria to power their fight against pathogens and tumors,” said senior author, , the William J. Ledger, M.D., Distinguished Associate Professor of Infection and Immunology in at Weill Cornell Medicine. “However, the molecular mechanisms that govern this critical energy supply are still not well understood.”

Lipids are abundant in ovarian tumors, but T cells seem unable to utilize them in this environment.

“Researchers have focused on a protein called fatty acid-binding protein 5, or FABP5, which facilitates lipid uptake, but its exact location within the T cell remained unclear,” said first author Sung-Min Hwang, a postdoctoral associate in Cubillos-Ruiz’s lab, who led the new study. Hwang discovered that in patient-derived tumor specimens and mouse models of ovarian cancer, FABP5 becomes trapped inside the cytoplasm of T cells instead of moving to the cell surface, where it would normally help take up lipids from the surroundings.

“That was the ‘aha!’ moment; since FABP5 is not getting to the surface, it couldn’t bring in the lipids necessary for energy production. But we still needed to figure out why,” said Cubillos-Ruiz, who is also co-leader of the Cancer Biology Program in the at Weill Cornell Medicine.

Working with collaborators, the researchers used a battery of biochemical assays to identify proteins that bind to FABP5. They found a protein called Transgelin 2 that interacts with FABP5 and helps move it to the cell surface.

Further experiments revealed that ovarian tumors somehow suppress the production of Transgelin 2 in infiltrating T cells. Delving deeper, the researchers discovered that the transcription factor XBP1, which is activated by the stressful conditions within the tumor, represses the gene encoding Transgelin 2. Without Transgelin 2, FABP5 cannot move to the surface of the T cells and pick up lipids, rendering the T cells unable to attack the tumor.

With this fundamental mechanism worked out, the team explored chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR T) cells, an immunotherapy. This approach collects a patient’s T cells, engineers them to attack tumor cells and then injects the designer cells into the patient. “CAR T cells work well against hematological cancers like leukemia and lymphoma, but they’re really not effective for solid tumors like ovarian or pancreatic cancers,” Cubillos-Ruiz said.

When Hwang and his colleagues tested CAR T cells, which are currently being evaluated in clinical trials, in mouse models of metastatic ovarian cancer, they found the same problem – Transgelin 2 repression and impaired lipid uptake. Just like normal T cells in the tumor microenvironment, the engineered CAR T cells had FABP5 tangled in the cytoplasm. As a result, the CAR T cells were unable access lipids for energy to effectively attack the tumor, highlighting a critical barrier in using this immunotherapy for solid tumors like ovarian cancer.

To solve the problem, the researchers inserted a modified Transgelin 2 gene that couldn’t be blocked by stress transcription factors induced by the tumor, so expression of the critical protein was preserved. This allowed Transgelin 2 to chaperone FABP5 to the surface of the CAR T cells where it could take up lipids.

Indeed, the upgraded T cells were much more effective in attacking ovarian tumors than the original CAR T cells. “Our findings reveal a key mechanism of immune suppression in ovarian cancer and suggest new avenues to improve the efficacy of adoptive T cell immunotherapies in aggressive solid malignancies,” Cubillos-Ruiz said.

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Defense, the American Association for Cancer Research and the AACR-Bristol Myers Squibb Immuno-Oncology Research Fellowship.