Until now, assistive dressing robots, designed to help an elderly person or a person with a disability get dressed, have been created in the laboratory as a one-armed machine, but research has shown that this can be uncomfortable for the person in care or impractical.

To tackle this problem, Dr Jihong Zhu, a robotics researcher at the University of York’s Institute for Safe Autonomy, proposed a , which has not been attempted in previous research, but who have demonstrated that specific actions are required to reduce discomfort and distress to the individual in their care.

It is thought that this technology could be significant in the social care system to allow care-workers to spend less time on practical tasks and more time on the health and mental well-being of individuals.

Observe and learn

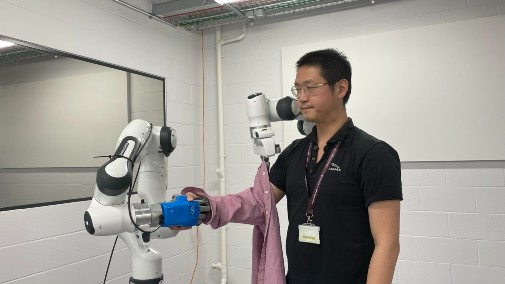

Dr Zhu gathered important information on how care-workers moved during a dressing exercise, through allowing a robot to observe and learn from human movements and then, through AI, generate a model that mimics how human helpers do their task.

This allowed the researchers to gather enough data to illustrate that two hands were needed for dressing and not one, as well as information on the angles that the arms make, and the need for a human to intervene and stop or alter certain movements.

Motion demo

Dr Zhu, from the University of York’s and the School of Physics, Engineering and Technology, said: “We know that practical tasks, such as getting dressed, can be done by a robot, freeing up a care-worker to concentrate more on providing companionship and observing the general well-being of the individual in their care. It has been tested in the laboratory, but for this to work outside of the lab we really needed to understand how care-workers did this task in real-time.

“We adopted a method called learning from demonstration, which means that you don’t need an expert to programme a robot, a human just needs to demonstrate the motion that is required of the robot and the robot learns that action. It was clear that for care workers two arms were needed to properly attend to the needs of individuals with different abilities.

“One hand holds the individual’s hand to guide them comfortably through the arm of a shirt, for example, whilst at the same time the other hand moves the garment up and around or over. With the current one-armed machine scheme a patient is required to do too much work in order for a robot to assist them, moving their arm up in the air or bending it in ways that they might not be able to do.”

Human modelling

The team were also able to build algorithms that made the robotic arm flexible enough in its movements for it to perform the pulling and lifting actions, but also be prevented from making an action by the gentle touch of a human hand, or guided out of an action by a human hand moving the hand left or right, up or down, without the robot resisting.

Dr Zhu said: “Human modelling can really help with efficient and safe human and robot interactions, but it is not only important to ensure it performs the task, but that it can be halted or changed mid-action should an individual desire it. Trust is a significant part of this process, and the next step in this research is testing the robot’s safety limitations and whether it will be accepted by those who need it most.”