“Beti hui hai (It’s a girl).”

Haryana’s Sunil Jaglan recalls how this trio of words and the nurse’s accompanying sombre expression changed his life in 2012. Not only did it swivel Jaglan’s attention to the issues of that grips villages in India, but it also transformed his mindset for the better.

Admittedly a former patriarch — “Of course, like other boys, I grew up observing my mother and sisters do chores in the home; while the men of the family went to work” — the birth of a baby girl was all it took to transform Jaglan into a feminist.

A quick look at the 43-year-old changemaker’s life tells me he has a soft spot for leadership roles. In his term as sarpanch (village head) of Bibipur in Jind district from 2010 to 2015, Jaglan set his sights on improving the village infrastructure. His ‘Gaav Bane Sheher Se Sundar’ campaign aimed to make Bibipur’s beauty parallel that of metropolitans.

That wasn’t all. Recalling a landmark initiative during his term as sarpanch, Jaglan shows off the official panchayat (village council) website created at the time. The first of its kind, the website offered netizens a comprehensive glimpse of the voters in the village, upgrades in infra, and the village’s history. “I used to be called the ,” he is proud of this moniker.

Sunil Jaglan is a social activist who advocates against female foeticide and girl-child inequality.

But it was the birth of his baby girl that compelled him to digress from his focus on village development to female foeticide. “I never imagined this path for my life,” he reminisces, thinking back to his days as a mathematics coach in his early 20s when working Sundays and the extra money was all he looked forward to.

From a youth with simple dreams, Jaglan has grown into the proud father of two daughters; teaching India’s generation of men to be better.

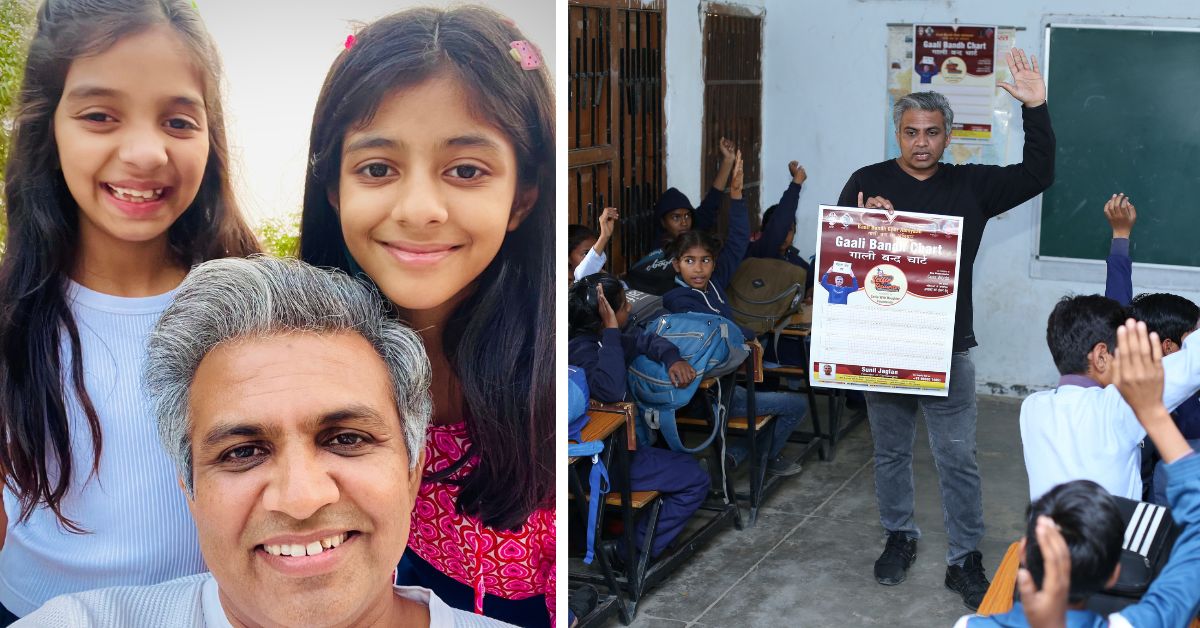

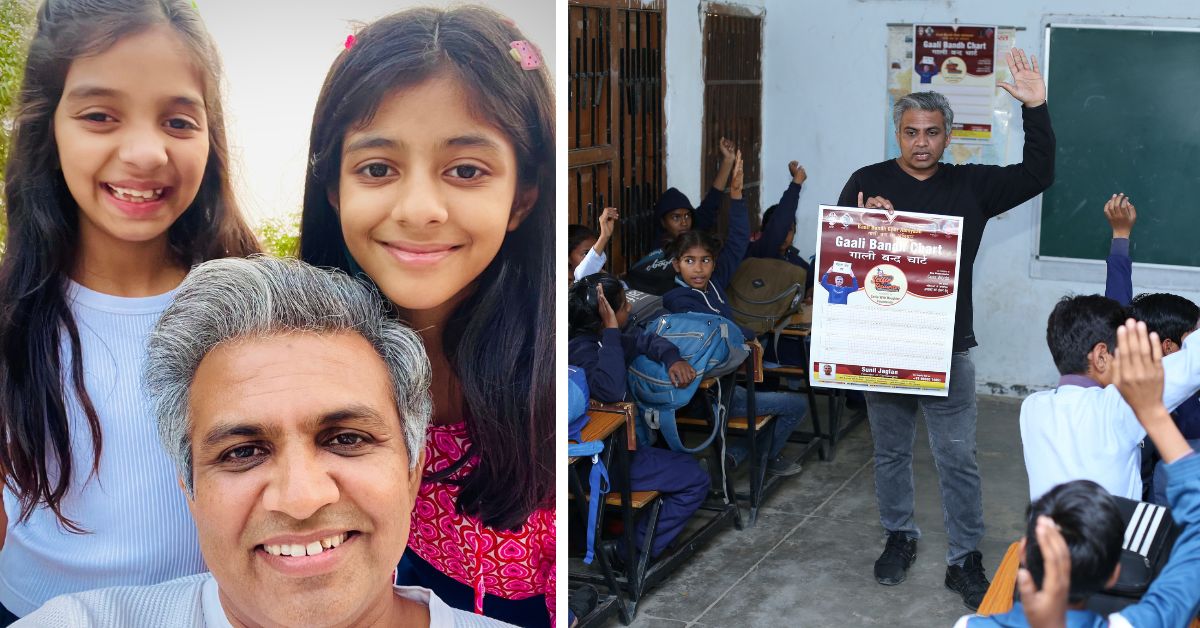

With every question I pose to Jaglan, I can hear two background voices nudging him when he muddles the details. It’s a school holiday for Nandini (12) and Yachika (10). Naturally, they have picked a spot beside their father for the interview. Having had a front-row seat to his , the duo are well-versed in the details.

“Often, they have also joined me in their own scope,” Jaglan mentions.

He shares anecdotes of how Nandini would urge her school friends to avoid using gaalis (Hindi swear words) — specifically those that referenced women — in tandem with her father’s launch of the ‘Gaali Bandh Ghar’ campaign in 2016.

Sunil Jaglan with his daughters Nandini and Yachika.

Meanwhile, Jaglan’s younger daughter sellotaped ‘period rule’ charts in the girls’ washroom at her school when she discovered that several girls never knew what a period was; how to use a pad; and how to dispose of one.

So, with the girls by his side, Jaglan tells me the story of the day it all started. “Nandini was born in 2012 on National Girl Child Day.” Initiated by the Government in 2008, the day was earmarked for spreading and the inequalities they have to endure.

The irony.

Jaglan recalls the day as one of the happiest of his life. But the nurse and doctor at the hospital begged to differ. “After the nurse delivered the news to me that I had become a father, I gave her a token as a thank-you gesture. She declined. She said, ‘The doctor will get angry. If you had a boy, we would accept it’.”

He dismissed this as a one-off incident, refusing to let it spoil his celebratory mood. “But when I started distributing sweets in the village, I realised there was a serious problem. First of all, people would assume that my distributing sweets meant I had a baby boy. So they would congratulate me on it.” When Jaglan told them he had become a father to a baby girl, their responses were usually consolatory. “Koi baat nahi, agli baar ladka hoga (Don’t worry. Next time you will get a son).”

And how would Jaglan respond to these unwarranted sympathies?

“I went and bought more mithai and celebrated for a month,” he smiles. “Then I went to the to check on the sex ratio.”

It was 832 females per 1,000 males in 2011. Some fact-checking on Haryana’s sex ratio through the years tells me Jaglan shouldn’t have been surprised at the numbers. The state has been (in)famous for having one of the worst sex ratios in India — a problem compounded by patriarchal mindsets prevalent in North India where raising a girl has sacrificial connotations.

But, 2023 statistics point out, that mindsets are seeing a shift — there were 916 females per 1,000 males.

At the time, however, Jaglan was horrified. He intended to discuss this issue with women at the next gram sabha meeting. So, you can only imagine his surprise when he discovered that Bibipur gram sabhas were a male-dominated scene. “Even if women had to pass by the spot where the meeting was being held, they would cover their heads in a ghoonghat (traditional headscarf),” Jaglan shares. The general consensus was that women were incapable of making . That power of autonomy rested with the men.

Sunil Jaglan encouraged women to be a part of khap panchayats in Bibipur to participate in village decisions.

Firm in his resolve to change this chauvinist mentality, Jaglan says he began urging women to be a part of chaupals (village meetings), supported by his wife, sisters, and mother. “In 2012, we set up one of India’s first women gram sabhas,” he shares. The ripple effect this had was tremendous, and Jaglan decided to go a step further.

He hosted a khap panchayat in 2012 in Bibipur. An unofficial meeting of clans across villages, khap panchayats are historically headed and attended by men. But the one that Jaglan hosted saw 2,000 women from across India convene to discuss the issues that oppressed their female counterparts.

A historic win!

Among the issues discussed were domestic violence, dowry (a payment given to the groom by the bride’s family during marriage), and pressure to abort baby girl foetuses.

The effects of the Bibipur model have trickled into Gurugram. As Ramchander, sarpanch of Makhrola village shares, “This model of village development was introduced in our village a year ago. While on paper, women had an equal participation in , the reality was very different. Their husbands would be attending in place of them. But now, women are not only called for assemblies, they actively participate in the panchayat.”

Sunil Jaglan spoke to women about their concerns regarding female foeticide, dowry, harassment and domestic violence.

Conversations with young brides in Bibipur led Jaglan to discover the painful existence they had. They listed a litany of atrocities ranging from repeated unnecessary ultrasounds — not aimed at ensuring the good health of the baby, but instead the sex; forced abortions when the ultrasound revealed a girl foetus; and starvation diets to kill the girl foetus when aborting wasn’t an option.

These issues formed the bedrock of Jaglan’s campaign ‘Nigrani Rakhna’. “The formula was simple — I listed mothers in Bibipur who were pregnant for the second, third or fourth time. The gram panchayat then assigned two women to each of these mothers who would . We wanted to instil fear in those who were pressuring the women to have sex determination tests.”

Sunil Jaglan is the former sarpanch of Bibipur village in Haryana.

In the meantime, Jaglan zeroed in on shops in Jind district claiming to have miraculous ways of conceiving a boy. “We shut down 12 of these and cracked down on illegal sex determination clinics.”

It wasn’t simply Jaglan’s professional work that was drawing acclaim. The birth of his daughter Yachika in 2014 — accompanied by Jaglan’s announcement that his family was now complete — drew praise from the village. It turned into an exemplar. “Many families who have daughters stopped thinking that they need to keep trying till they got a son. In fact, I know of many men who had a vasectomy done as they don’t want more children. They are happy with their daughters.”

Through his advocacy work, Sunil Jaglan has created awareness in thousands of villages in Haryana, Uttarakhand and Rajasthan.

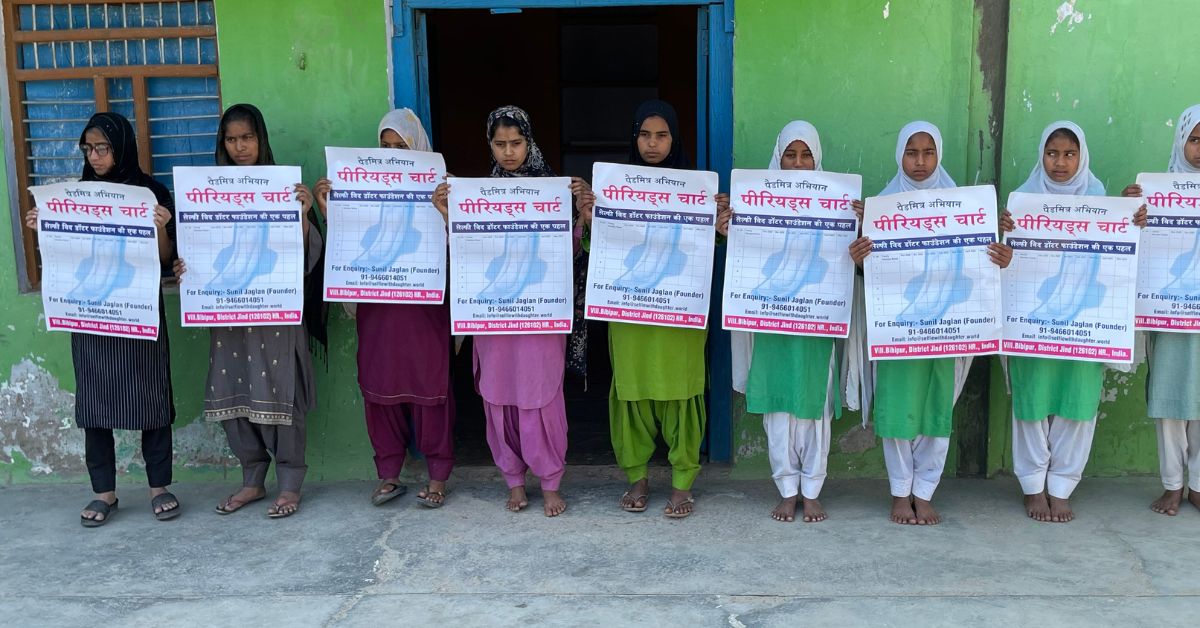

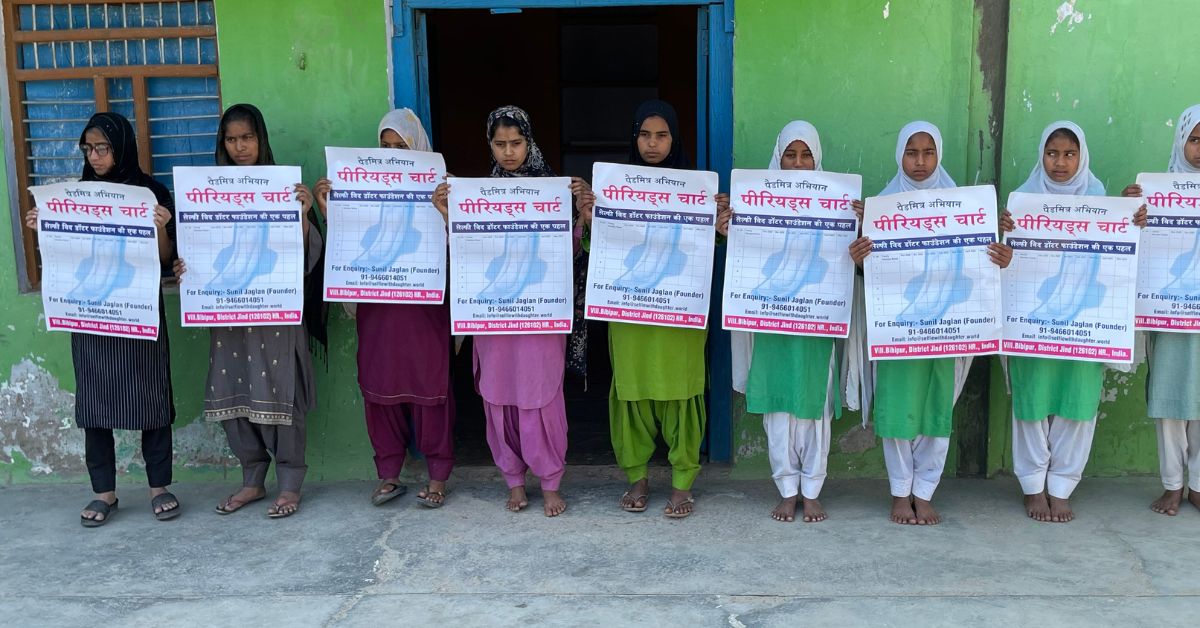

The is taboo in the villages of India. Women speak about it in hushed tones, while men are evasive, treating the topic as something mythical. Pads are wrapped in black paper, and menstruating women are exiled to live in gudlus (thatched huts) where they are at the mercy of nature.

Many areas of remote India haven’t come to terms with periods yet.

Now turn your gaze to Bibipur, which is an outlier. Here, thousands of homes have a calendar bearing big red circles, denoting the date on which the woman of the home got her last period. This is a part of the ‘Periods Chart Campaign’ started in 2020 by Jaglan to not only get the conversation going around menstruation but also to alert parents when their daughters were showing irregular cycles.

The period chart concept has been implemented in over 40,000 village homes across Haryana to help women track their menstrual cycles.

The women of Bibipur have period charts on which they track their cycles and also become aware of vaginal infections and other conditions.

Supriya Biwal is thrilled as she takes me through her own journey of setting up a chart in the hallroom. Having closely worked with Jaglan for three years now, Supriya has had a close glance at the . “My brother and father did not know about periods. But I made charts for my mother, aunty, and myself, and put them up on the wall.”

“Log jhijhakte the (People were hesitant to talk about these things),” she says. “But now my brother and father speak about periods comfortably.”

Jaglan and his team did not stop at charts. “We spoke to the parents and daughters about vaginal infection, sanitary pads, diet, and nutrition. We also started conversations with men about menopause. Many of them thought of it as a time when the period cycle stopped. But they did not know about its emotional implications.”

The Lado Pustakalayas and Lado Panchayats have been a great success with women being encouraged to study further and take part in governing bodies.

Supriya’s personal favourite was the ‘Daughter’s Nameplate’ campaign. It advocated for the daughter’s names to be listed on the home porch. “I found it interesting because usually, the nameplates have the names of the dada (paternal grandfather) or father.” Supriya proudly states that the nameplate of her home boasts her name. “I did not stop at my home. I made a similar nameplate for many other women too,” she shares.

Ticking his other campaigns off a mental checklist, Jaglan sheds light on the ‘Lado Pustakalaya’ initiative through which in five villages of Haryana; the ‘Beti Padhao Abhiyan’ which coaxed girls’ parents to let their daughters complete their education instead of marrying them off early; and of course, the most viral ‘Selfie With Daughter’ (2015) campaign, which received mention from Prime Minister Narendra Modi as well as former president Pranab Mukherjee.

Sunil Jaglan worked closely with former President Pranab Mukherjee to extend the Bibipur village development model to other states.

Celebrities and iconic personalities jumped onto the bandwagon uploading a selfie with their daughter in tune with the campaign’s messaging of giving special recognition to girl children to allow them to grow to become empowered human beings.

Additionally, Jaglan popularised the concept of the ‘Lado Panchayats’, urging women to take a stand for their issues. “The village chaupals began seeing a lot of women. I would encourage illiterate women to go up on stage and speak about their concerns; this was revolutionary.”

While the ‘Selfie With Daughter’ campaign started by Sunil Jaglan was a success, he has initiated many more awareness campaigns to empower women.

Witnessing the scope and scale of his work, the Government leaned into his model and Jaglan recalls working with former president Pranab Mukherjee. “I became a senior consultant at the Pranab Mukherjee Foundation. My role was to replicate the Bibipur model of across India.”

If you are reading this story, Jaglan has asked me to convey something:

He doesn’t want for you to assume he was born with a superhero cape. “I was and am ordinary. It is the pain of the women in my life that transformed me. My goal is that one day when the squeals of a baby girl are heard in rural India, the only response should be smiles,” he remarks.

Edited by Pranita Bhat

Haryana’s Sunil Jaglan recalls how this trio of words and the nurse’s accompanying sombre expression changed his life in 2012. Not only did it swivel Jaglan’s attention to the issues of that grips villages in India, but it also transformed his mindset for the better.

Admittedly a former patriarch — “Of course, like other boys, I grew up observing my mother and sisters do chores in the home; while the men of the family went to work” — the birth of a baby girl was all it took to transform Jaglan into a feminist.

A quick look at the 43-year-old changemaker’s life tells me he has a soft spot for leadership roles. In his term as sarpanch (village head) of Bibipur in Jind district from 2010 to 2015, Jaglan set his sights on improving the village infrastructure. His ‘Gaav Bane Sheher Se Sundar’ campaign aimed to make Bibipur’s beauty parallel that of metropolitans.

That wasn’t all. Recalling a landmark initiative during his term as sarpanch, Jaglan shows off the official panchayat (village council) website created at the time. The first of its kind, the website offered netizens a comprehensive glimpse of the voters in the village, upgrades in infra, and the village’s history. “I used to be called the ,” he is proud of this moniker.

Sunil Jaglan is a social activist who advocates against female foeticide and girl-child inequality.

But it was the birth of his baby girl that compelled him to digress from his focus on village development to female foeticide. “I never imagined this path for my life,” he reminisces, thinking back to his days as a mathematics coach in his early 20s when working Sundays and the extra money was all he looked forward to.

From a youth with simple dreams, Jaglan has grown into the proud father of two daughters; teaching India’s generation of men to be better.

A baby girl melts a patriarch’s heart

With every question I pose to Jaglan, I can hear two background voices nudging him when he muddles the details. It’s a school holiday for Nandini (12) and Yachika (10). Naturally, they have picked a spot beside their father for the interview. Having had a front-row seat to his , the duo are well-versed in the details.

“Often, they have also joined me in their own scope,” Jaglan mentions.

He shares anecdotes of how Nandini would urge her school friends to avoid using gaalis (Hindi swear words) — specifically those that referenced women — in tandem with her father’s launch of the ‘Gaali Bandh Ghar’ campaign in 2016.

Sunil Jaglan with his daughters Nandini and Yachika.

Meanwhile, Jaglan’s younger daughter sellotaped ‘period rule’ charts in the girls’ washroom at her school when she discovered that several girls never knew what a period was; how to use a pad; and how to dispose of one.

So, with the girls by his side, Jaglan tells me the story of the day it all started. “Nandini was born in 2012 on National Girl Child Day.” Initiated by the Government in 2008, the day was earmarked for spreading and the inequalities they have to endure.

The irony.

Jaglan recalls the day as one of the happiest of his life. But the nurse and doctor at the hospital begged to differ. “After the nurse delivered the news to me that I had become a father, I gave her a token as a thank-you gesture. She declined. She said, ‘The doctor will get angry. If you had a boy, we would accept it’.”

He dismissed this as a one-off incident, refusing to let it spoil his celebratory mood. “But when I started distributing sweets in the village, I realised there was a serious problem. First of all, people would assume that my distributing sweets meant I had a baby boy. So they would congratulate me on it.” When Jaglan told them he had become a father to a baby girl, their responses were usually consolatory. “Koi baat nahi, agli baar ladka hoga (Don’t worry. Next time you will get a son).”

And how would Jaglan respond to these unwarranted sympathies?

“I went and bought more mithai and celebrated for a month,” he smiles. “Then I went to the to check on the sex ratio.”

It was 832 females per 1,000 males in 2011. Some fact-checking on Haryana’s sex ratio through the years tells me Jaglan shouldn’t have been surprised at the numbers. The state has been (in)famous for having one of the worst sex ratios in India — a problem compounded by patriarchal mindsets prevalent in North India where raising a girl has sacrificial connotations.

But, 2023 statistics point out, that mindsets are seeing a shift — there were 916 females per 1,000 males.

At the time, however, Jaglan was horrified. He intended to discuss this issue with women at the next gram sabha meeting. So, you can only imagine his surprise when he discovered that Bibipur gram sabhas were a male-dominated scene. “Even if women had to pass by the spot where the meeting was being held, they would cover their heads in a ghoonghat (traditional headscarf),” Jaglan shares. The general consensus was that women were incapable of making . That power of autonomy rested with the men.

Sunil Jaglan encouraged women to be a part of khap panchayats in Bibipur to participate in village decisions.

Firm in his resolve to change this chauvinist mentality, Jaglan says he began urging women to be a part of chaupals (village meetings), supported by his wife, sisters, and mother. “In 2012, we set up one of India’s first women gram sabhas,” he shares. The ripple effect this had was tremendous, and Jaglan decided to go a step further.

He hosted a khap panchayat in 2012 in Bibipur. An unofficial meeting of clans across villages, khap panchayats are historically headed and attended by men. But the one that Jaglan hosted saw 2,000 women from across India convene to discuss the issues that oppressed their female counterparts.

A historic win!

Among the issues discussed were domestic violence, dowry (a payment given to the groom by the bride’s family during marriage), and pressure to abort baby girl foetuses.

The effects of the Bibipur model have trickled into Gurugram. As Ramchander, sarpanch of Makhrola village shares, “This model of village development was introduced in our village a year ago. While on paper, women had an equal participation in , the reality was very different. Their husbands would be attending in place of them. But now, women are not only called for assemblies, they actively participate in the panchayat.”

Sunil Jaglan spoke to women about their concerns regarding female foeticide, dowry, harassment and domestic violence.

‘Dadi chahegi toh poti aayegi’

Conversations with young brides in Bibipur led Jaglan to discover the painful existence they had. They listed a litany of atrocities ranging from repeated unnecessary ultrasounds — not aimed at ensuring the good health of the baby, but instead the sex; forced abortions when the ultrasound revealed a girl foetus; and starvation diets to kill the girl foetus when aborting wasn’t an option.

These issues formed the bedrock of Jaglan’s campaign ‘Nigrani Rakhna’. “The formula was simple — I listed mothers in Bibipur who were pregnant for the second, third or fourth time. The gram panchayat then assigned two women to each of these mothers who would . We wanted to instil fear in those who were pressuring the women to have sex determination tests.”

Sunil Jaglan is the former sarpanch of Bibipur village in Haryana.

In the meantime, Jaglan zeroed in on shops in Jind district claiming to have miraculous ways of conceiving a boy. “We shut down 12 of these and cracked down on illegal sex determination clinics.”

It wasn’t simply Jaglan’s professional work that was drawing acclaim. The birth of his daughter Yachika in 2014 — accompanied by Jaglan’s announcement that his family was now complete — drew praise from the village. It turned into an exemplar. “Many families who have daughters stopped thinking that they need to keep trying till they got a son. In fact, I know of many men who had a vasectomy done as they don’t want more children. They are happy with their daughters.”

Through his advocacy work, Sunil Jaglan has created awareness in thousands of villages in Haryana, Uttarakhand and Rajasthan.

Leaning into the idea of a new India

The is taboo in the villages of India. Women speak about it in hushed tones, while men are evasive, treating the topic as something mythical. Pads are wrapped in black paper, and menstruating women are exiled to live in gudlus (thatched huts) where they are at the mercy of nature.

Many areas of remote India haven’t come to terms with periods yet.

Now turn your gaze to Bibipur, which is an outlier. Here, thousands of homes have a calendar bearing big red circles, denoting the date on which the woman of the home got her last period. This is a part of the ‘Periods Chart Campaign’ started in 2020 by Jaglan to not only get the conversation going around menstruation but also to alert parents when their daughters were showing irregular cycles.

The period chart concept has been implemented in over 40,000 village homes across Haryana to help women track their menstrual cycles.

The women of Bibipur have period charts on which they track their cycles and also become aware of vaginal infections and other conditions.

Supriya Biwal is thrilled as she takes me through her own journey of setting up a chart in the hallroom. Having closely worked with Jaglan for three years now, Supriya has had a close glance at the . “My brother and father did not know about periods. But I made charts for my mother, aunty, and myself, and put them up on the wall.”

“Log jhijhakte the (People were hesitant to talk about these things),” she says. “But now my brother and father speak about periods comfortably.”

Jaglan and his team did not stop at charts. “We spoke to the parents and daughters about vaginal infection, sanitary pads, diet, and nutrition. We also started conversations with men about menopause. Many of them thought of it as a time when the period cycle stopped. But they did not know about its emotional implications.”

The Lado Pustakalayas and Lado Panchayats have been a great success with women being encouraged to study further and take part in governing bodies.

Supriya’s personal favourite was the ‘Daughter’s Nameplate’ campaign. It advocated for the daughter’s names to be listed on the home porch. “I found it interesting because usually, the nameplates have the names of the dada (paternal grandfather) or father.” Supriya proudly states that the nameplate of her home boasts her name. “I did not stop at my home. I made a similar nameplate for many other women too,” she shares.

Ticking his other campaigns off a mental checklist, Jaglan sheds light on the ‘Lado Pustakalaya’ initiative through which in five villages of Haryana; the ‘Beti Padhao Abhiyan’ which coaxed girls’ parents to let their daughters complete their education instead of marrying them off early; and of course, the most viral ‘Selfie With Daughter’ (2015) campaign, which received mention from Prime Minister Narendra Modi as well as former president Pranab Mukherjee.

Sunil Jaglan worked closely with former President Pranab Mukherjee to extend the Bibipur village development model to other states.

Celebrities and iconic personalities jumped onto the bandwagon uploading a selfie with their daughter in tune with the campaign’s messaging of giving special recognition to girl children to allow them to grow to become empowered human beings.

Additionally, Jaglan popularised the concept of the ‘Lado Panchayats’, urging women to take a stand for their issues. “The village chaupals began seeing a lot of women. I would encourage illiterate women to go up on stage and speak about their concerns; this was revolutionary.”

While the ‘Selfie With Daughter’ campaign started by Sunil Jaglan was a success, he has initiated many more awareness campaigns to empower women.

Witnessing the scope and scale of his work, the Government leaned into his model and Jaglan recalls working with former president Pranab Mukherjee. “I became a senior consultant at the Pranab Mukherjee Foundation. My role was to replicate the Bibipur model of across India.”

If you are reading this story, Jaglan has asked me to convey something:

He doesn’t want for you to assume he was born with a superhero cape. “I was and am ordinary. It is the pain of the women in my life that transformed me. My goal is that one day when the squeals of a baby girl are heard in rural India, the only response should be smiles,” he remarks.

Edited by Pranita Bhat