Chemical dyes wield a significant but often overlooked impact on India’s environment. In the bustling textile industry, where colours flourish, the widespread

presents a multifaceted threat to the environment.

These dyes, laden with heavy metals and toxic compounds, find their way into water bodies, soil, and air, polluting crucial natural resources. They not only pollute nature but also affect the food chain in water bodies.

As per a research paper by Science Direct, “ also act as toxic, mutagenic and carcinogenic agents, persist as environmental pollutants and cross entire food chains providing biomagnification, such that organisms at higher trophic levels show higher levels of contamination compared to their prey.”

Alternatives such as using flowers to make colours and textile dyes have been gaining popularity, but they come with a set of challenges including availability, chances of fading and cost.

“There is also an issue of colour consistency. The textile industry needs the colour to be of the same consistency on every cloth which becomes difficult with says Vaishali Kulkarni of KBCols Sciences.

KBCols is a science company that makes natural dyes. Co-founded by Vaishali Kulkarni and her husband Aryan Singh, the company has figured out a way of making natural dyes from waste by using microbes!

How does the science behind this work? The founders explain the intricacies in an interview with The Better India.

Born and raised in Mumbai, Maharashtra, Vaishali informs she never planned that she would become an entrepreneur. “I am a science person but the turn of events led me into the colour industry,” she says.

After completing her postgraduate studies, she decided to opt for a PhD from a college in Mumbai.

“During my PhD studies, projects often came to our college concerning the treatment of coloured water in the textile department. Researchers were tasked with addressing this issue by employing various unit operations to purify the water. It became evident that prevention was better than cure,” she ponders.

This gave me an idea about how she could instead of trying to purify the contaminated water.

Vaishali Kulkarni and her husband Aryan Singh, co-founders of KBCols Sciences.

It was during this time that she met Aryan, who had a similar idea.

“We aimed to tackle the root cause rather than deal with the consequences. This led us to the realisation that instead of managing the release of harmful colours into the water after their use in textiles and other industries, it would be more prudent to develop safer alternatives. This idea sparked our interest, and we began working on it diligently,” she informs.

Once the PhD was complete, she decided to try and secure a grant from the government.

“We applied for a grant, and it was awarded to KDCols to conduct proof-of-concept (POC) studies. As per the grant requirements, we had to select an incubator centre if we didn’t have access to a lab or any specific topics in mind,” she recalls.

“The nearest one to Mumbai was in Pune, where the Venture Center provided this facility. Consequently, we were incubated there, and our journey began in earnest in 2018,” she adds.

The company was founded by the duo the same year, and they have been working ever since to make organic colours from waste.

“We all know that colours are ubiquitous, found in nearly every industry, including textiles, foods, and cosmetics. We often associate specific colours with certain products, like the expectation that apples should be red. Consequently, colour plays a significant role in our day-to-day activities,” ponder Vaishali.

With about 80 percent of the industries in the world using chemical dyes, they are affecting our petroleum resources too.

“These dyes are primarily derived from petroleum resources, which are finite. Therefore, it’s inevitable that one day, these petroleum resources will become exhausted. An effective alternative was the need of the hour,” she says.

In today’s market, options in the form of vegetable and flower colours are available, but they lack sustainability.

“They require vast amounts of land for cultivation. For instance, growing specific crops or flowers necessitates extensive land resources and is often subject to seasonal variations, taking months to mature,” she says.

One of the primary challenges faced by the industry with these flower and vegetable colours is their lack of reproducibility. Their colours vary, making it difficult to achieve consistency. This inconsistency prevents their widespread adoption on an industrial scale.

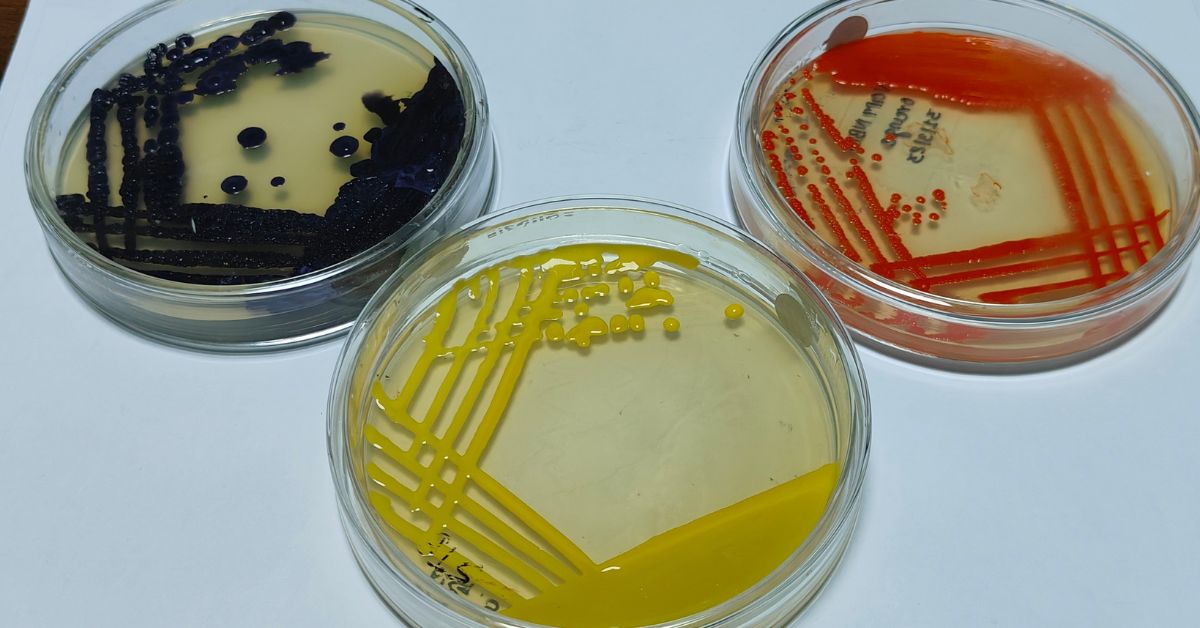

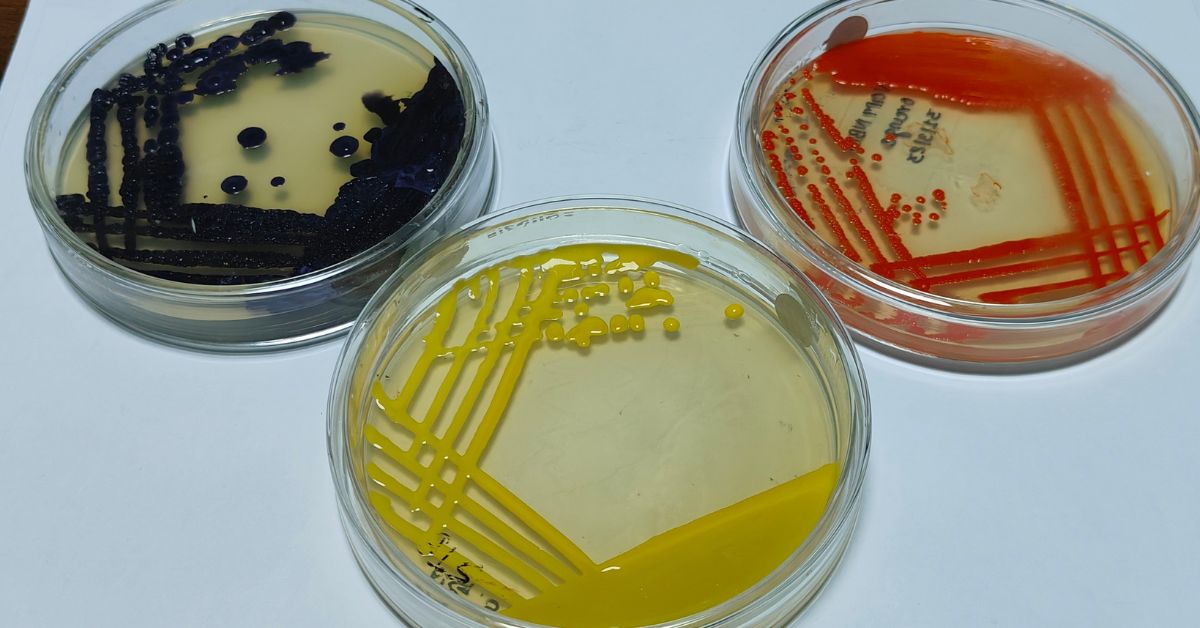

These colours are made using microbes derived from waste.

“To address this issue, the duo decided to use micro-organisms. Our colours are natural bio-colours, offering a reliable and sustainable solution to the challenges posed by traditional vegetable and flower colours,” she states.

The raw materials to make these colours are derived from waste.

“Microorganisms possess inherent properties that enable them to produce colours, as reported in the literature. However, despite this knowledge, no one in India has ventured into industrial or commercial production using this method,” she says.

Recognising this untapped potential, the duo decided to explore this area and offer natural colour options.

“Our approach involves utilising a blend of plant or vegetable colours. These colours can be cultivated within a vertical reactor, allowing for efficient production within a batch time of 16 to 24 hours,” she says.

She continues, “Remarkably, this process does not rely on petroleum resources or high temperatures for cultivation. Instead, along with sugars and salts, to cultivate the microorganisms within the reactor.”

Talking about the research and development process, she talks about the limitations that come with using microbes.

“Microorganisms tend to produce colour when subjected to stress. Therefore, we must collect samples from various environments where microorganisms are naturally exposed to stressors. To isolate the pigmented microorganisms from the multitude of bacteria and microorganisms involves collecting soil samples and screening water and air samples from diverse locations. Remarkably, even a tiny amount of soil, just one milligram, can yield thousands of microbes,” she says.

She adds, “While this research and development phase is time-consuming, once we have successfully isolated a microbe with a desired colour, it becomes a valuable proprietary asset of the company.”

Isolating microbes being a time-consuming process is what has delayed the couple from launching their products in the market.

“We previously collaborated with a designer based in Pune, to launch a small collection. This collection was showcased at the Lakme Fashion Week 2022 in Delhi, where models wore garments dyed with our colours. While this served as a soft launch, our official commercial launch is scheduled for either the end of this year or the next,” she informs.

Talking about how their colours are competitive with the synthetic colours in the market, Vaishali explains, “In textiles, the performance parameters are based on three aspects: colour fastness to light, washing, and rubbing. Colour fastness to light refers to the fabric’s ability to resist fading when exposed to sunlight. Washing fastness assesses how well the colour holds up when subjected to harsh detergents. Rubbing fastness measures the colour stability of the fabric under friction.”

The company collaborated with a Pune designer to make apparel using their dyes.

For each parameter, industrial standards typically range from 1 to 5, with a higher value indicating better performance.

“Chemical colours often score a perfect 5, while our natural colours typically achieve a rating of 3 to 4 for light fastness and 5 for washing fastness which is an acceptable industry standard,” she says.

Sharing her future plans, Vaishali informs that the duo is focused on launching the product as soon as possible.

“Currently, we are also in the process of constructing our demonstration plant in Pune, with an estimated capacity of around 500 kg per month. This expansion aims to increase our production capacity. Additionally, we plan to diversify into the cosmetics and food sectors, in addition to textiles,” she shares.

Want to know more about their ingenious technology? Visit website to know more.

(Edited by Padmashree Pande)

These dyes, laden with heavy metals and toxic compounds, find their way into water bodies, soil, and air, polluting crucial natural resources. They not only pollute nature but also affect the food chain in water bodies.

As per a research paper by Science Direct, “ also act as toxic, mutagenic and carcinogenic agents, persist as environmental pollutants and cross entire food chains providing biomagnification, such that organisms at higher trophic levels show higher levels of contamination compared to their prey.”

Alternatives such as using flowers to make colours and textile dyes have been gaining popularity, but they come with a set of challenges including availability, chances of fading and cost.

“There is also an issue of colour consistency. The textile industry needs the colour to be of the same consistency on every cloth which becomes difficult with says Vaishali Kulkarni of KBCols Sciences.

KBCols is a science company that makes natural dyes. Co-founded by Vaishali Kulkarni and her husband Aryan Singh, the company has figured out a way of making natural dyes from waste by using microbes!

How does the science behind this work? The founders explain the intricacies in an interview with The Better India.

‘This was destiny’

Born and raised in Mumbai, Maharashtra, Vaishali informs she never planned that she would become an entrepreneur. “I am a science person but the turn of events led me into the colour industry,” she says.

After completing her postgraduate studies, she decided to opt for a PhD from a college in Mumbai.

“During my PhD studies, projects often came to our college concerning the treatment of coloured water in the textile department. Researchers were tasked with addressing this issue by employing various unit operations to purify the water. It became evident that prevention was better than cure,” she ponders.

This gave me an idea about how she could instead of trying to purify the contaminated water.

Vaishali Kulkarni and her husband Aryan Singh, co-founders of KBCols Sciences.

It was during this time that she met Aryan, who had a similar idea.

“We aimed to tackle the root cause rather than deal with the consequences. This led us to the realisation that instead of managing the release of harmful colours into the water after their use in textiles and other industries, it would be more prudent to develop safer alternatives. This idea sparked our interest, and we began working on it diligently,” she informs.

Once the PhD was complete, she decided to try and secure a grant from the government.

“We applied for a grant, and it was awarded to KDCols to conduct proof-of-concept (POC) studies. As per the grant requirements, we had to select an incubator centre if we didn’t have access to a lab or any specific topics in mind,” she recalls.

“The nearest one to Mumbai was in Pune, where the Venture Center provided this facility. Consequently, we were incubated there, and our journey began in earnest in 2018,” she adds.

The company was founded by the duo the same year, and they have been working ever since to make organic colours from waste.

“We all know that colours are ubiquitous, found in nearly every industry, including textiles, foods, and cosmetics. We often associate specific colours with certain products, like the expectation that apples should be red. Consequently, colour plays a significant role in our day-to-day activities,” ponder Vaishali.

With about 80 percent of the industries in the world using chemical dyes, they are affecting our petroleum resources too.

“These dyes are primarily derived from petroleum resources, which are finite. Therefore, it’s inevitable that one day, these petroleum resources will become exhausted. An effective alternative was the need of the hour,” she says.

In today’s market, options in the form of vegetable and flower colours are available, but they lack sustainability.

“They require vast amounts of land for cultivation. For instance, growing specific crops or flowers necessitates extensive land resources and is often subject to seasonal variations, taking months to mature,” she says.

Using microbes to make colours

One of the primary challenges faced by the industry with these flower and vegetable colours is their lack of reproducibility. Their colours vary, making it difficult to achieve consistency. This inconsistency prevents their widespread adoption on an industrial scale.

These colours are made using microbes derived from waste.

“To address this issue, the duo decided to use micro-organisms. Our colours are natural bio-colours, offering a reliable and sustainable solution to the challenges posed by traditional vegetable and flower colours,” she states.

The raw materials to make these colours are derived from waste.

“Microorganisms possess inherent properties that enable them to produce colours, as reported in the literature. However, despite this knowledge, no one in India has ventured into industrial or commercial production using this method,” she says.

Recognising this untapped potential, the duo decided to explore this area and offer natural colour options.

“Our approach involves utilising a blend of plant or vegetable colours. These colours can be cultivated within a vertical reactor, allowing for efficient production within a batch time of 16 to 24 hours,” she says.

She continues, “Remarkably, this process does not rely on petroleum resources or high temperatures for cultivation. Instead, along with sugars and salts, to cultivate the microorganisms within the reactor.”

Talking about the research and development process, she talks about the limitations that come with using microbes.

“Microorganisms tend to produce colour when subjected to stress. Therefore, we must collect samples from various environments where microorganisms are naturally exposed to stressors. To isolate the pigmented microorganisms from the multitude of bacteria and microorganisms involves collecting soil samples and screening water and air samples from diverse locations. Remarkably, even a tiny amount of soil, just one milligram, can yield thousands of microbes,” she says.

She adds, “While this research and development phase is time-consuming, once we have successfully isolated a microbe with a desired colour, it becomes a valuable proprietary asset of the company.”

How did it translate in the market?

Isolating microbes being a time-consuming process is what has delayed the couple from launching their products in the market.

“We previously collaborated with a designer based in Pune, to launch a small collection. This collection was showcased at the Lakme Fashion Week 2022 in Delhi, where models wore garments dyed with our colours. While this served as a soft launch, our official commercial launch is scheduled for either the end of this year or the next,” she informs.

Talking about how their colours are competitive with the synthetic colours in the market, Vaishali explains, “In textiles, the performance parameters are based on three aspects: colour fastness to light, washing, and rubbing. Colour fastness to light refers to the fabric’s ability to resist fading when exposed to sunlight. Washing fastness assesses how well the colour holds up when subjected to harsh detergents. Rubbing fastness measures the colour stability of the fabric under friction.”

The company collaborated with a Pune designer to make apparel using their dyes.

For each parameter, industrial standards typically range from 1 to 5, with a higher value indicating better performance.

“Chemical colours often score a perfect 5, while our natural colours typically achieve a rating of 3 to 4 for light fastness and 5 for washing fastness which is an acceptable industry standard,” she says.

Sharing her future plans, Vaishali informs that the duo is focused on launching the product as soon as possible.

“Currently, we are also in the process of constructing our demonstration plant in Pune, with an estimated capacity of around 500 kg per month. This expansion aims to increase our production capacity. Additionally, we plan to diversify into the cosmetics and food sectors, in addition to textiles,” she shares.

Want to know more about their ingenious technology? Visit website to know more.

(Edited by Padmashree Pande)