Paulina Soto isn’t sure what she wants to do with her life. But the third-year Arizona State University student knows one thing.

The Bachelor of Arts degree she’s pursuing in , offered by the humanities division in The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, will help her no matter her career path.

“I don’t want to be boxed into one sort of thing, and CTE gives me so many different avenues that I feel like even if I’m not sure what I want to do, I’m going to be prepared for whatever I do in the future.”

The CTE degree, which launched last fall, is the first degree that draws from all three of the large, interdisciplinary schools of the humanities: the , the and the

Students are encouraged to take a humanistic approach to world issues surrounding culture, environment and technology. This fall, the degree program will be offered online.

Regents Professor , who leads the program, said the degree is in part a response to the belief that a humanities degree does not lead to a productive career.

“Although ASU is a bit of an exception in this, nationwide and indeed globally, there’s been a huge falling off of enrollment in humanities subjects,” Bate said. “The main reason for that is parents and students feel, ‘How is this going to get me a job? What is the practical use of my history degree, my philosophy degree, my literature degree?’

“At the same time, young people are passionate about many of the big problems facing the world. We believe that these big problems of culture, technology and environment need a holistic approach. Of course, they also need scientists, social scientists and policymakers, but they also need the ideas, the tools, the skills and the wisdom that comes from humanities disciplines.”

Using humanities as a method to tackle urgent issues in the world is not a new approach. Bate said former President Bill Clinton, more than a half-dozen British prime ministers as well as prime ministers from India and Pakistan took classes under a degree at Oxford University in Oxford, England, called PPE — for politics, philosophy and economics.

“In the 20th century, it was really a great foundational degree for public leadership,” Bate said. “In some sense, I’d like to imagine CTE as kind of a 21st century equivalent of that.”

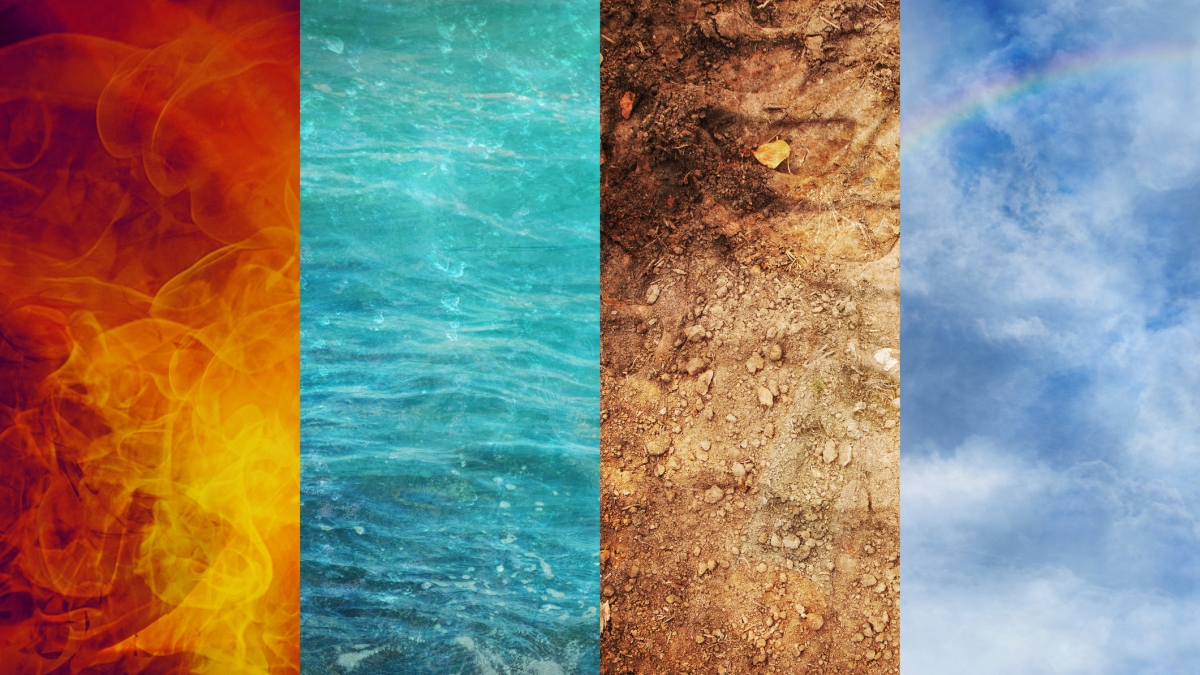

This spring, Bate taught CTE 310, which brings historical, humanistic and transdisciplinary understanding to the four ancient elements: earth, air, fire and water. As an example of how humanities can be applied to multiple career paths, Bate talked about the debate regarding deep-sea mining in the Pacific ocean.

A lot of the rare earth minerals found at the bottom of the ocean, Bate said, will be crucial for developing alternative energy sources. But, he wondered, which nation has the right to mine them? And how does that impact the Indigenous people who live on the islands in the Pacific Ocean and depend on fishing for their livelihood?

“One could imagine a pre-law student who’s interested in environmental law really taking hold of that sort of topic,” Bate said.

Bate also recognized the need for students to have experiential learning opportunities. In addition to internships, he recognized how complementary the transdisciplinary, high-impact, social challenge-driven learning was to CTE and how it would provide CTE students a culminating experience to synthesize, integrate and apply the knowledge and skills they’ve developed from the program.

Related stories

• Author, scholar, director, poet

• transforms in-class research into real-world impact

The Humanities Lab, like the CTE degree program, vanguards the importance of including humanist approaches related to ethics, values, culture, history, storytelling, power and diversity — with the intention of developing new inquiry-based approaches that demonstrate how principled innovation can help us re-imagine more equitable, healthy and sustainable communities.

Faculty from the English department and the School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies co-teach with faculty from across the university in the Humanities Lab on CTE-themed courses like , , , and .

“I think there’s a lot of evidence for cultural and indeed environmental elements of the mental health crisis of our time,” Bate said. “I think the study of cultures, the use of the arts, are tools that can really help us deal with issues around depression and anxiety, and those social aspects of mental health. I think it would be ideal for students in that pipeline to medicine.”

Jacob Melkus doesn’t plan to be a lawyer or a doctor. But as a fourth-year student majoring in anthropology, he appreciated the deeper understanding the CTE 310 class gave him about today’s world issues.

“I was able to articulate my thoughts more,” Melkus said. “Before, I was just like, ‘Here’s how I feel about something.’ But I didn’t necessarily have the education to back up my thoughts.”

Here’s the bottom line, as Bate sees it: Whether you’re a student interested in medicine, law, anthropology — really, any subject — humanities training will contribute to your career.

“What we’re trying to do, really, is flip the model of humanities training,” he said. “By reconfiguring a humanities degree, beginning with the problems and applying the traditional knowledge, we reinvigorate the disciplines and we address the big problems of the world.”