Author Gaura Pant ‘Shivani’, in her book Amader Shantiniketan, recalled Santiniketan as “a peaceful retreat that remained unshaken by the din and terror of the world beyond.” And through the course of history, scholars, writers, students, historians, and even simple admirers, have recalled the neighbourhood — which was founded by

— in similar ways, as a land that transcends the bounds of religion, regions, caste, and any such limitations that tend to divide us.

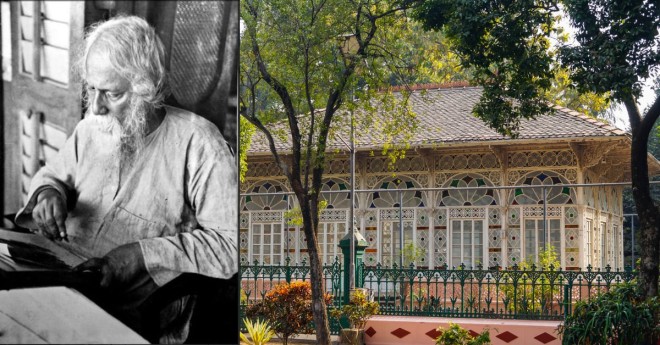

The university town, located in Birbhum district’s Bolpur town, is among West Bengal’s — and India’s — most important heritage icons. A campaign to give it a place on UNESCO’s list of World Heritage Sites first began in 2010, when the Archeological Survey of India submitted a formal request to the UN body to include parts of the neighbourhood in the list.

Author Gaura Pant recalled Santiniketan as “a peaceful retreat that remained unshaken by the din and terror of the world beyond.”

The bid had failed then, but last week, began inching closer to a revival when the International Council of Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) — the advisory body to the UNESCO World Heritage Centre — made a recommendation to include it on the list based on a file moved by the Government of India. If selected, Santiniketan will be the state’s second cultural symbol to make it to UNESCO’s list — in 2021,

Santiniketan embodied polymath Rabindranath Tagore’s vision for education that explored and challenged the boundaries of traditional classrooms. In recent years, it has moved away from this dream, but the UNESCO recognition could perhaps set it back on its path.

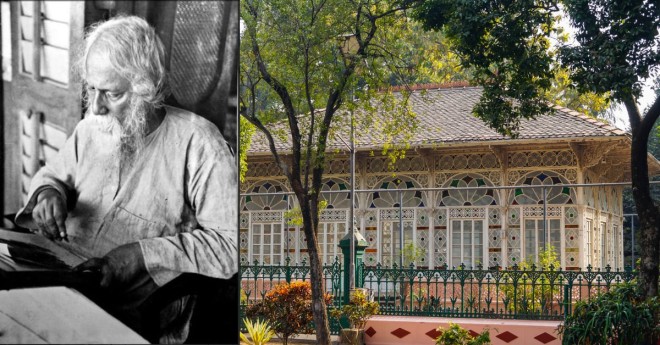

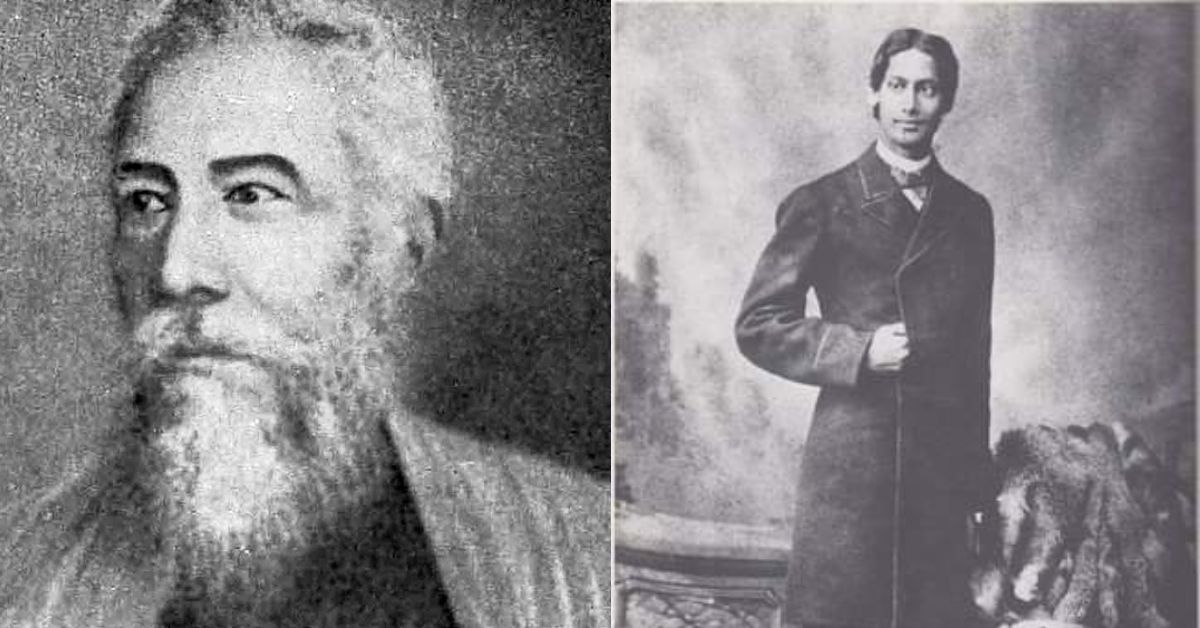

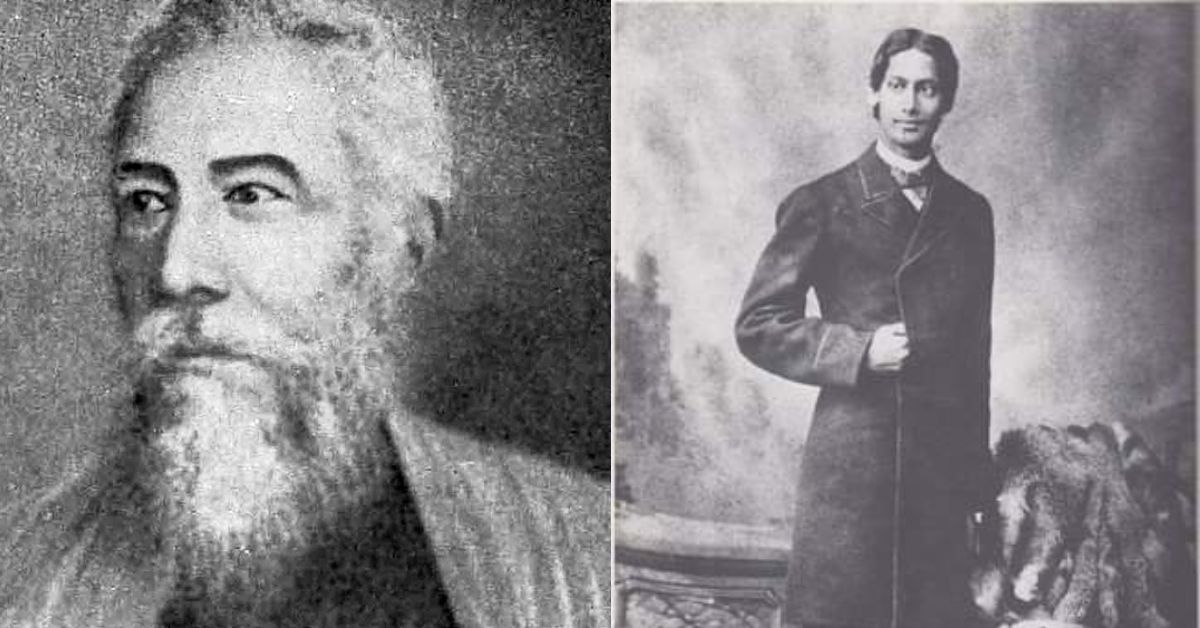

In the 1860s, Tagore’s father Debendranath was traversing western Bengal. When he arrived in the Birbhum region, he was instantly captivated by the beauty of the land, where “two large Chhatim (Alstonia scholaris) trees [offered] gentle shade on the dry, red land”. It is said that he took 20 acres of the land on permanent lease from its then owner Bhuban Mohan Sinha, who was the talukdar of Raipur. Here, he built a guest house and christened it Santiniketan, or the “abode of peace”.

Santiniketan embodied polymath Rabindranath Tagore’s vision for education that explored and challenged the boundaries of traditional classrooms.

Years later, in a trust deed drawn in 1888, Debendranath would say the land would allow “no insult to any religion or religious deity”, and “apart from worshipping the formless, no community may worship any idol depicting god, man, or animals; neither may anyone arrange sacrificial rituals in Santiniketan”.

Bolpur, the region where Santiniketan came up, was no more remarkable than any other town at the time. A portion of the town was owned by the Sinha family, who developed a village named Bhubandanga in the area, which was known for a group of violent dacoits. It is said that they eventually surrendered to Debendranath and helped him develop the area. Here, the ‘maharshi’ built a 60 x 30 foot glass structure for Brahmo prayers, right under the Chhatim trees that had first captivated him.

Debendranath Tagore (left), the father of Rabindranath Tagore, built a guest house and christened it Santiniketan, or the “abode of peace”. (Source: Wikipedia, )

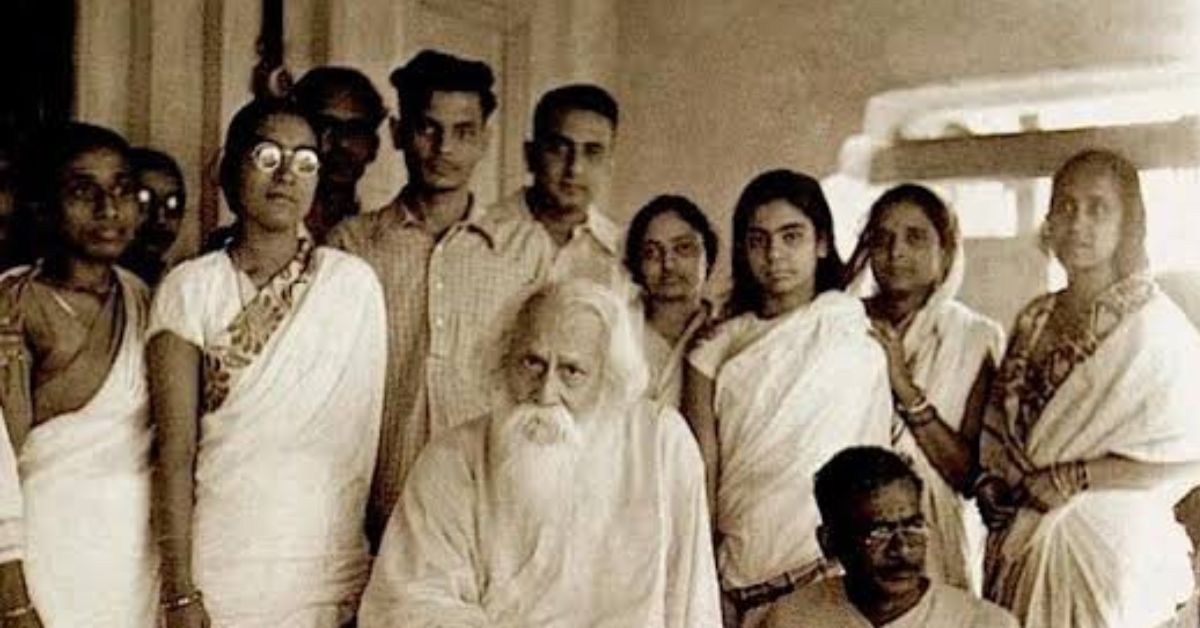

Tagore arrived at Shantiniketan for the first time at the age of 17.

Around this time, he had gone to London to become a barrister but had returned a short while later, without a degree. The time he had spent in London, however, was not in vain — though he did not fully embrace English traditions and culture, he also stayed away from his family’s stringent Hindu religious practices, instead walking a path in the middle, incorporating his learnings and experiences from both cultures.

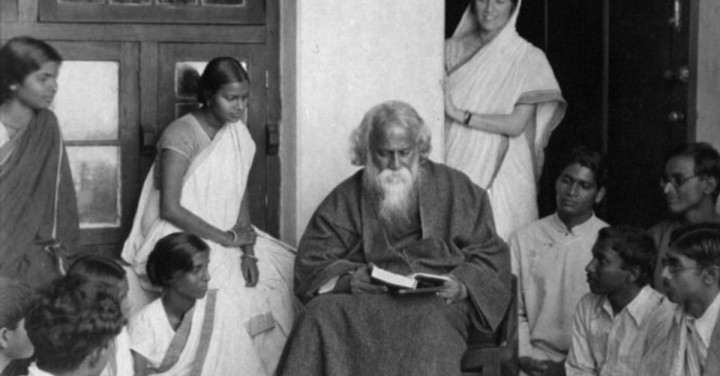

It’s no secret that the laureate was a fierce critic of limiting education to a classroom. “Education is a permanent adventure of life,” he would say. For him, could deliver far more to students than the rote, textual learning that the European model of education had ushered in.

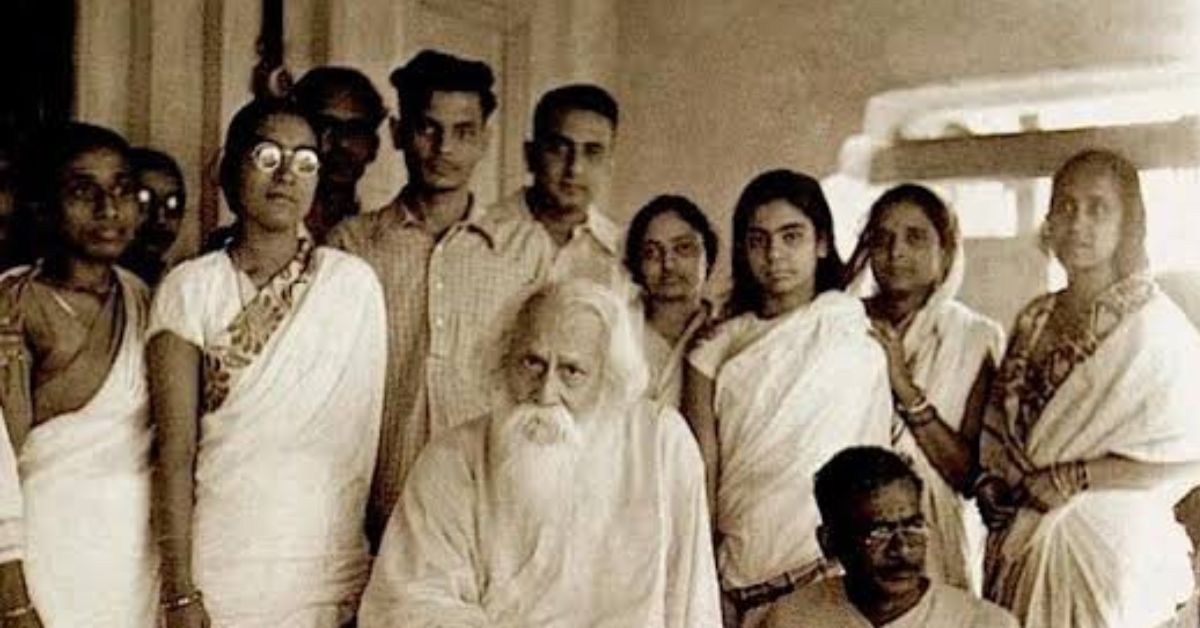

So in 1921, Tagore sought to build a new form of university — “I have in mind to make Santiniketan the connecting thread between India and the world,” he said. “I have to found a world centre for the study of humanity there… I want to make that place somewhere beyond the limits of nation and geography.”

In 1921, Tagore sought to build a new form of university — “the connecting thread between India and the world.” ( )

What the college envisioned was evident in its name — Visva Bharati, or the confluence of the world with India. It began as a school named Brahmacharyashram with just five students in 1901, with the purpose to inculcate the development of the mind, inspired by ancient India’s tapovan. In 1921, it was formally established as a university and rechristened Visva Bharati.

Santiniketan and Visva Bharati aligned with Tagore’s early years of walking that middle path between the two worlds that had taught him so much — his school was by no means to denounce Western education, but instead to uphold the ideals of India’s culture and tradition, retaining the best of both worlds. It also pioneered a coeducational model in India, which was nearly unheard of at the time.

What the college envisioned was evident in its name — Visva Bharati, or the confluence of the world with India.

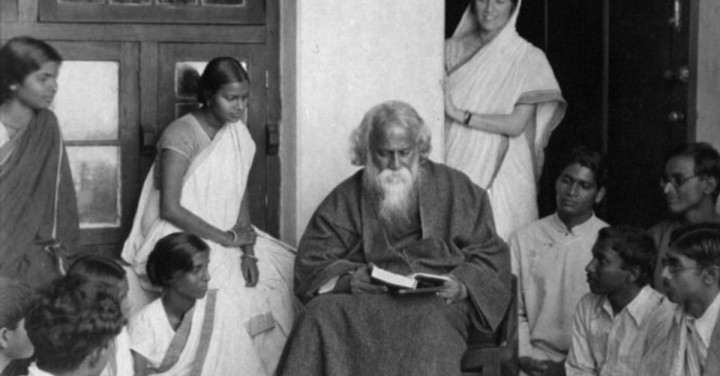

The Statesman noted that teachers at the school taught students by posing questions to them, rather than relying on lectures alone. “Students were encouraged to deliberate about their life decisions and to take the initiative in organising meetings.”

The report added, “Tagore urged students to explore intellectual self-reliance and freedom. He believed that true freedom in the acquisition of knowledge and experience could not be gained by ‘possessing other people’s ideas but by forming one’s own standards of judgement and producing one’s own thoughts’.”

“Students were encouraged to deliberate about their life decisions and to take the initiative in organising meetings.”

Though a bit far from Tagore’s original ideals, in some ways, Visva Bharati retains the ethos on which it was built by the polymath. It is known for its focus on humanities and arts, as a haven that still looks beyond the confines of religions, genders or varying cultures; where thousands of students still study under trees and commute within the campus on cycles; and where historic structures serve as both tourist attractions and functional facilities for students.

Over the years, it has seen notable alumni members — from and Amartya Sen to and Gayatri Devi. It contributed to the making of India’s national emblem when Kala Bhavan (Visva Bharati’s art school) director Nandalal Bose assigned five students to design it.

Beyond the school, there is the Rabindra Bhavan — a museum and centre that houses a major portion of the laureate’s life in the forms of letters, manuscripts, paintings, writings, journals, and photographs. Its Uttarayana Complex houses five homes built by Tagore that imbibe the sustainable architectural practices of rural India, and the Ashram Complex — Santiniketan’s oldest area — houses mud and coal structures and several historic homes.

Every year, the neighbourhood marks the harvest season with the Poush Mela, a portal into rural Bengal’s history. About 15 km away is Amar Kutir, once a refuge for Indian revolutionaries and today a cooperative society for rural arts and crafts.

Handmade ornaments from rural Bengal, at Sonajhurir Haat.

Holi celebrations at Santiniketan

About 15 km away is Amar Kutir, once a refuge for Indian revolutionaries and today a cooperative society for rural arts and crafts.

Santiniketan was the place where Tagore wrote some of his best works, and where he discovered that he would be the first Indian to receive the Nobel Prize.

It can be said that ‘Chitto Jetha Bhayshunyo’ (Where the Mind is Without Fear), which is regarded as Tagore’s vision for a “new and awakened India”, also embodies his work with Santiniketan — where education would lead young Indians to freedom of the mind, where studying is accompanied closely by the joy of learning, and where a person grows from within.

Santiniketan was the place where Tagore wrote some of his best works, and where he discovered that he would be the first Indian to receive the Nobel Prize.

When you rummage through Tagore’s lifelong work, you find its unique ability to find a place in both the university classrooms of intellectuals and scholars, as well as the narrow lanes, cluttered homes, and blooming fields of the rural class. Santiniketan embodied something similar — a place where the ethos and principles laid down in ancient India actually end up paving the way for global assimilation and universality.

But in its bid to gain its place on UNESCO’s list, it has to be acknowledged in its entirety — including its tangible elements.

Abha Narain Lambah, who prepared the ASI dossier back in 2010, noted that “Santiniketan was unique and uniquely challenging as a UNESCO dossier, because apart from the overarching narrative of Tagore as a visionary artist and thinker, under the UNESCO format, we had to argue on the cultural criteria of tangible elements.”

She also noted, “In the early 20th century, India was under the yoke of colonialism, and Santiniketan heralded a break from colonial revivalist architecture to forge a new modernity, which was not looking to the West but inwards, exploring indigenous materials and techniques, delving into India’s rich past and absorbing influences from the East to create a pan-Asian modernity.”

Meanwhile, historian Tapati Guha-Thakurta noted that the UNESCO recognition could perhaps restore the international eminence that the place enjoyed.

In a letter to Gandhi during his later years, Tagore would define Santiniketan as a “vessel, carrying the cargo of [his] ‘life’s best treasure’.”

Perhaps it’s time to unpack this cargo and explore within, to see why Santiniketan is integral to India’s history, not only thanks to the legacy and contributions of Tagore but also as an individual entity that ushered a new dawn of India’s cultural glory.

Edited by Pranita Bhat

The university town, located in Birbhum district’s Bolpur town, is among West Bengal’s — and India’s — most important heritage icons. A campaign to give it a place on UNESCO’s list of World Heritage Sites first began in 2010, when the Archeological Survey of India submitted a formal request to the UN body to include parts of the neighbourhood in the list.

Author Gaura Pant recalled Santiniketan as “a peaceful retreat that remained unshaken by the din and terror of the world beyond.”

The bid had failed then, but last week, began inching closer to a revival when the International Council of Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) — the advisory body to the UNESCO World Heritage Centre — made a recommendation to include it on the list based on a file moved by the Government of India. If selected, Santiniketan will be the state’s second cultural symbol to make it to UNESCO’s list — in 2021,

Santiniketan embodied polymath Rabindranath Tagore’s vision for education that explored and challenged the boundaries of traditional classrooms. In recent years, it has moved away from this dream, but the UNESCO recognition could perhaps set it back on its path.

A barren land and two Chhatim trees

In the 1860s, Tagore’s father Debendranath was traversing western Bengal. When he arrived in the Birbhum region, he was instantly captivated by the beauty of the land, where “two large Chhatim (Alstonia scholaris) trees [offered] gentle shade on the dry, red land”. It is said that he took 20 acres of the land on permanent lease from its then owner Bhuban Mohan Sinha, who was the talukdar of Raipur. Here, he built a guest house and christened it Santiniketan, or the “abode of peace”.

Santiniketan embodied polymath Rabindranath Tagore’s vision for education that explored and challenged the boundaries of traditional classrooms.

Years later, in a trust deed drawn in 1888, Debendranath would say the land would allow “no insult to any religion or religious deity”, and “apart from worshipping the formless, no community may worship any idol depicting god, man, or animals; neither may anyone arrange sacrificial rituals in Santiniketan”.

Bolpur, the region where Santiniketan came up, was no more remarkable than any other town at the time. A portion of the town was owned by the Sinha family, who developed a village named Bhubandanga in the area, which was known for a group of violent dacoits. It is said that they eventually surrendered to Debendranath and helped him develop the area. Here, the ‘maharshi’ built a 60 x 30 foot glass structure for Brahmo prayers, right under the Chhatim trees that had first captivated him.

A permanent adventure of life

Debendranath Tagore (left), the father of Rabindranath Tagore, built a guest house and christened it Santiniketan, or the “abode of peace”. (Source: Wikipedia, )

Tagore arrived at Shantiniketan for the first time at the age of 17.

Around this time, he had gone to London to become a barrister but had returned a short while later, without a degree. The time he had spent in London, however, was not in vain — though he did not fully embrace English traditions and culture, he also stayed away from his family’s stringent Hindu religious practices, instead walking a path in the middle, incorporating his learnings and experiences from both cultures.

It’s no secret that the laureate was a fierce critic of limiting education to a classroom. “Education is a permanent adventure of life,” he would say. For him, could deliver far more to students than the rote, textual learning that the European model of education had ushered in.

So in 1921, Tagore sought to build a new form of university — “I have in mind to make Santiniketan the connecting thread between India and the world,” he said. “I have to found a world centre for the study of humanity there… I want to make that place somewhere beyond the limits of nation and geography.”

In 1921, Tagore sought to build a new form of university — “the connecting thread between India and the world.” ( )

The path in the middle

What the college envisioned was evident in its name — Visva Bharati, or the confluence of the world with India. It began as a school named Brahmacharyashram with just five students in 1901, with the purpose to inculcate the development of the mind, inspired by ancient India’s tapovan. In 1921, it was formally established as a university and rechristened Visva Bharati.

Santiniketan and Visva Bharati aligned with Tagore’s early years of walking that middle path between the two worlds that had taught him so much — his school was by no means to denounce Western education, but instead to uphold the ideals of India’s culture and tradition, retaining the best of both worlds. It also pioneered a coeducational model in India, which was nearly unheard of at the time.

What the college envisioned was evident in its name — Visva Bharati, or the confluence of the world with India.

The Statesman noted that teachers at the school taught students by posing questions to them, rather than relying on lectures alone. “Students were encouraged to deliberate about their life decisions and to take the initiative in organising meetings.”

The report added, “Tagore urged students to explore intellectual self-reliance and freedom. He believed that true freedom in the acquisition of knowledge and experience could not be gained by ‘possessing other people’s ideas but by forming one’s own standards of judgement and producing one’s own thoughts’.”

And what is Santiniketan today?

“Students were encouraged to deliberate about their life decisions and to take the initiative in organising meetings.”

Though a bit far from Tagore’s original ideals, in some ways, Visva Bharati retains the ethos on which it was built by the polymath. It is known for its focus on humanities and arts, as a haven that still looks beyond the confines of religions, genders or varying cultures; where thousands of students still study under trees and commute within the campus on cycles; and where historic structures serve as both tourist attractions and functional facilities for students.

Over the years, it has seen notable alumni members — from and Amartya Sen to and Gayatri Devi. It contributed to the making of India’s national emblem when Kala Bhavan (Visva Bharati’s art school) director Nandalal Bose assigned five students to design it.

Beyond the school, there is the Rabindra Bhavan — a museum and centre that houses a major portion of the laureate’s life in the forms of letters, manuscripts, paintings, writings, journals, and photographs. Its Uttarayana Complex houses five homes built by Tagore that imbibe the sustainable architectural practices of rural India, and the Ashram Complex — Santiniketan’s oldest area — houses mud and coal structures and several historic homes.

Every year, the neighbourhood marks the harvest season with the Poush Mela, a portal into rural Bengal’s history. About 15 km away is Amar Kutir, once a refuge for Indian revolutionaries and today a cooperative society for rural arts and crafts.

Handmade ornaments from rural Bengal, at Sonajhurir Haat.

Holi celebrations at Santiniketan

About 15 km away is Amar Kutir, once a refuge for Indian revolutionaries and today a cooperative society for rural arts and crafts.

Santiniketan was the place where Tagore wrote some of his best works, and where he discovered that he would be the first Indian to receive the Nobel Prize.

It can be said that ‘Chitto Jetha Bhayshunyo’ (Where the Mind is Without Fear), which is regarded as Tagore’s vision for a “new and awakened India”, also embodies his work with Santiniketan — where education would lead young Indians to freedom of the mind, where studying is accompanied closely by the joy of learning, and where a person grows from within.

‘My life’s best treasure’

Santiniketan was the place where Tagore wrote some of his best works, and where he discovered that he would be the first Indian to receive the Nobel Prize.

When you rummage through Tagore’s lifelong work, you find its unique ability to find a place in both the university classrooms of intellectuals and scholars, as well as the narrow lanes, cluttered homes, and blooming fields of the rural class. Santiniketan embodied something similar — a place where the ethos and principles laid down in ancient India actually end up paving the way for global assimilation and universality.

But in its bid to gain its place on UNESCO’s list, it has to be acknowledged in its entirety — including its tangible elements.

Abha Narain Lambah, who prepared the ASI dossier back in 2010, noted that “Santiniketan was unique and uniquely challenging as a UNESCO dossier, because apart from the overarching narrative of Tagore as a visionary artist and thinker, under the UNESCO format, we had to argue on the cultural criteria of tangible elements.”

She also noted, “In the early 20th century, India was under the yoke of colonialism, and Santiniketan heralded a break from colonial revivalist architecture to forge a new modernity, which was not looking to the West but inwards, exploring indigenous materials and techniques, delving into India’s rich past and absorbing influences from the East to create a pan-Asian modernity.”

Meanwhile, historian Tapati Guha-Thakurta noted that the UNESCO recognition could perhaps restore the international eminence that the place enjoyed.

In a letter to Gandhi during his later years, Tagore would define Santiniketan as a “vessel, carrying the cargo of [his] ‘life’s best treasure’.”

Perhaps it’s time to unpack this cargo and explore within, to see why Santiniketan is integral to India’s history, not only thanks to the legacy and contributions of Tagore but also as an individual entity that ushered a new dawn of India’s cultural glory.

Edited by Pranita Bhat