Nestled in the foothills of the Eastern Himalayas where the Brahmaputra river meandered through the verdant valleys of Assam, Neelam Dutta embarked on an extraordinary quest.

Neelam was not your ordinary villager; he possessed a deep reverence for the land and its treasures. With each passing day, he witnessed the subtle yet undeniable shifts in the climate, sensing the looming threat it posed to the cherished crops of his ancestors.

Determined to safeguard their legacy, he meticulously tended to a collection of seeds, each a precious heirloom from generations past. These seeds, once abundant, were now disappearing — victims of modernisation and the relentless march of time.

But Neelam refused to let them fade into obscurity. He understood that in the face of a changing climate, adaptation was key, and these heirlooms held the secrets to survival. His endeavour became a symbol of resilience, a guardian of tradition in a rapidly evolving world.

“Heirloom seeds, passed down for at least 50 years, are resistant to floods. This is a vital trait in combating food security threats posed by climate change,” Neelam, now 37, tells The Better India, “However, sadly, due to the increasing adoption of genetically modified hybrid seeds, farmers in the Northeast are abandoning heirloom varieties. This, coupled with frequent floods, has made agriculture unsustainable in the region.”

Neelam says he wanted the local farmers in his region to wholeheartedly adopt and switch to heirloom seeds.

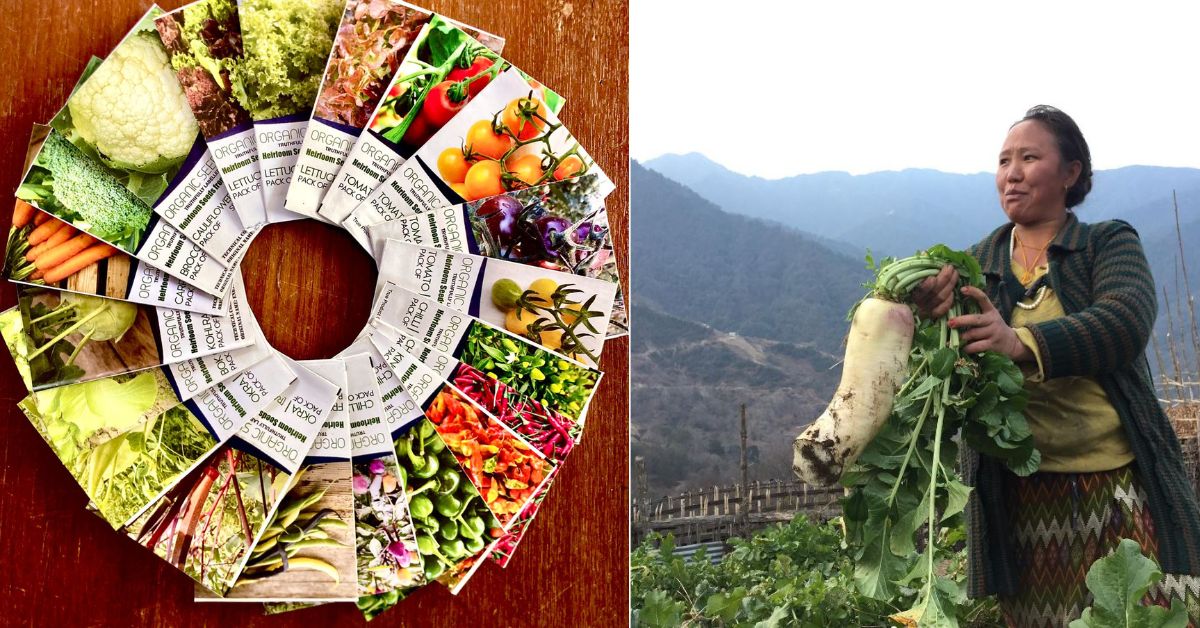

“In my opinion, the solution lies in preserving these heirloom seeds, which serve as an essential resource for farmers striving to adjust to climate change. I wanted to show them why it’s important to conserve our agricultural heritage,” says Neelam, who went on to promote the cultivation of heirloom seeds in his region. So far, he has conserved over 1,000 heirloom seed varieties of vegetables and rice, and trained at least 24,000 other farmers in seed conservation.

He claims his company ‘Pabhoi Greens’ is “the first seed conservation company in the Northeast” where farmers are propagating the organic seeds on their own. “Every time, these farmers grow heirloom seeds, they preserve that diversity and ensure these seeds are available for future generations,” he remarks.

Since childhood, Neelam recalls being compelled to study due to societal pressure. “I’m a farm boy!” he adds, “I wanted to pursue a career in agriculture like my father. He was a medical doctor by profession but quit his job to farm in the village.” But sadly, Neelam’s father passed away from a stroke while Neelam was studying in Class 11.

“After completing Class 12, I applied for graduation in arts from an open school. However, I was so disinterested that I neglected to submit assignments required to complete the degree,” shares the Pabhoi village resident.

Heirloom seeds are genetically diverse, don’t require chemical-laden fertilisers, and are naturally resistant to disease and pests.

In 2001, he inherited 18 acres of land from his father. Around the same time, he read Rachel Carson’s book ‘Silent Spring’, which highlighted the environmental harm caused by the indiscriminate use of pesticides. Motivated by Carson’s message, Neelam resolved to transition his land into an organic farm. By 2003, he had successfully converted his entire acreage to organic cultivation.

“After switching to organic farming, I found out there were no organic seed varieties available in the market. While some were accessible for rice, none were available for vegetables. The absence of reserves or authenticity in seed sources was concerning. Instead, the market was saturated with genetically modified hybrid seeds. This was a big worrying factor,” he says.

That’s when he also observed that most of the farmers in the Northeast were switching to hybrid seeds and overlooked . “After the Green Revolution, it was clear that only hybrid seeds were to be supplied to the market to the farmers. This was never a solution for an ‘evergreen’ revolution,” he opines.

“While hybrid seeds offer higher yields in one season, they cannot be saved for the following year. Consequently, farmers neglected heirloom seeds, leading to a loss of their sovereignty over time,” he points out. Since then, Neelam’s mission has been to conserve decade-old seeds for future generations.

Backed by the traditional wisdom imparted by his father and the elderly in the village, he set out in search of these heirloom treasures. In the past 15 years, Neelam has conserved nearly 800 varieties of vegetables like tomatoes, chillies, capsicum, basil, and 200 — including madhuri, nanyya rice, sticky gum rice, black rice, soft rice, and joha.

“These seeds have their own identity in terms of taste, colour, and shape. They are adaptable to the diverse Indian climatic zones. In one way, they are more resilient than hybrid seeds,” he says.

Neelam says he wanted the local farmers in his region to wholeheartedly adopt and switch to heirloom seeds.

Explaining the difference between hybrid and heirloom seeds, Neelam says, “While hybrid varieties give more yield, they are produced via genetic manipulation. We compel hybrid seeds to grow using external fertilisers and chemicals.”

“Farmers in Punjab, Western Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Haryana are extremely dependent on these outside inputs,” he adds.

Neelam further points out that, unlike heirloom varieties, the seed saved from hybrids does not grow true to its type in the next cycle. “They will be less vigorous and more genetically variable. If you cannot replicate it, there is no point in keeping the seeds. It only compels farmers to buy new seeds every year,” he says.

“Meanwhile, heirloom seeds are genetically diverse, don’t require chemical-laden fertilisers, and are naturally resistant to disease and pests. As they are open-pollinated, you can easily replicate those seeds next year,” he informs.

Giving an example of how the produce harvested from both varieties differ, Neelam says, “Today, tomatoes are available year-round, unlike in the past when we only had them in winter. To satisfy demand, farmers now grow tomatoes in mountainous areas with heavy fertiliser use. However, organically grown tomatoes in their respective seasons may not last as long but are richer in nutrients, tastier, and more vibrant in colour.”

He continues, “In France, various tomato varieties were once used in different recipes, but now a single, sweeter tomato is used universally, replacing the sour ones of the past.”

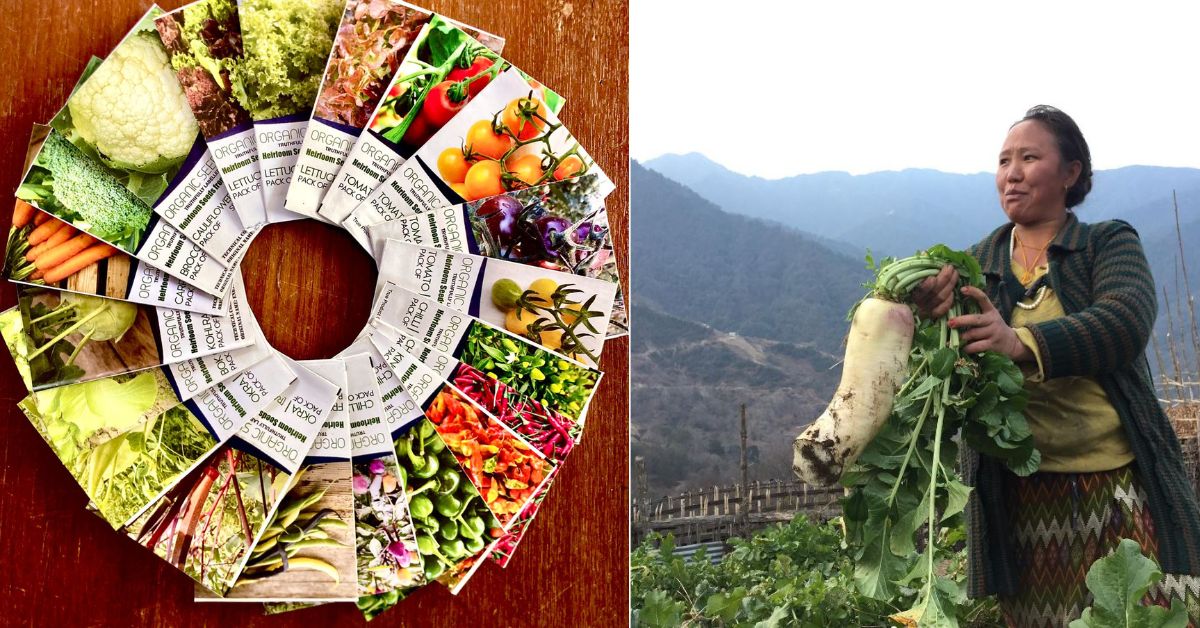

Neelam has trained 24,000 farmers across the Northeast.

Neelam says he wanted the local farmers in his region to wholeheartedly adopt and switch to heirloom seeds. “Otherwise there’s no point doing all this work,” he says, adding that his work received a great response from the community.

So, going beyond conserving seeds at an individual level, Neelam now trains thousands of farmers in seed conservation. So far, he has trained 24,000 farmers across the Northeast — including states like Nagaland and Arunachal Pradesh — helping them grow and conserve their own heirloom seeds.

Each year, Neelam sells approximately 8,000 packets of heirloom seeds at Rs 99 each to farmers. With these seeds and the training he provides, farmers can cultivate crops and harvest new seeds for the next cycle, ensuring sustainable food security — a goal Neelam passionately pursues to this day.

For the past 10 years, Diganata Bora has been cultivating vegetables using such heirloom seeds on his two-acre farm in Paschim Manjiri village of Assam.

“Compared to hybrid varieties, we get good yield using heirloom ones. In a bigha [0.33 acre], we now get 6-7 quintals of vegetables over 2-2.5 quintals. Additionally, our input expenses of Rs 40,000 have been reduced to zero as we use readily available cow dung as fertiliser. I am so happy to have decided to switch; now our soil fertility has also improved,” Diganata tells The Better India.

Neelam concludes, “Back when I began , there were no resources available for me to learn from. Now, I’m happy to have created a helpful platform for other farmers. When I visit their fields, I feel great to see the joy on their faces. By cultivating their own organic seeds and crops, they’ve made agriculture economically viable in our region.”

Edited by Pranita Bhat; All photos: Neelam Dutta.

Neelam was not your ordinary villager; he possessed a deep reverence for the land and its treasures. With each passing day, he witnessed the subtle yet undeniable shifts in the climate, sensing the looming threat it posed to the cherished crops of his ancestors.

Determined to safeguard their legacy, he meticulously tended to a collection of seeds, each a precious heirloom from generations past. These seeds, once abundant, were now disappearing — victims of modernisation and the relentless march of time.

But Neelam refused to let them fade into obscurity. He understood that in the face of a changing climate, adaptation was key, and these heirlooms held the secrets to survival. His endeavour became a symbol of resilience, a guardian of tradition in a rapidly evolving world.

“Heirloom seeds, passed down for at least 50 years, are resistant to floods. This is a vital trait in combating food security threats posed by climate change,” Neelam, now 37, tells The Better India, “However, sadly, due to the increasing adoption of genetically modified hybrid seeds, farmers in the Northeast are abandoning heirloom varieties. This, coupled with frequent floods, has made agriculture unsustainable in the region.”

Neelam says he wanted the local farmers in his region to wholeheartedly adopt and switch to heirloom seeds.

“In my opinion, the solution lies in preserving these heirloom seeds, which serve as an essential resource for farmers striving to adjust to climate change. I wanted to show them why it’s important to conserve our agricultural heritage,” says Neelam, who went on to promote the cultivation of heirloom seeds in his region. So far, he has conserved over 1,000 heirloom seed varieties of vegetables and rice, and trained at least 24,000 other farmers in seed conservation.

He claims his company ‘Pabhoi Greens’ is “the first seed conservation company in the Northeast” where farmers are propagating the organic seeds on their own. “Every time, these farmers grow heirloom seeds, they preserve that diversity and ensure these seeds are available for future generations,” he remarks.

Quest of a farm boy

Since childhood, Neelam recalls being compelled to study due to societal pressure. “I’m a farm boy!” he adds, “I wanted to pursue a career in agriculture like my father. He was a medical doctor by profession but quit his job to farm in the village.” But sadly, Neelam’s father passed away from a stroke while Neelam was studying in Class 11.

“After completing Class 12, I applied for graduation in arts from an open school. However, I was so disinterested that I neglected to submit assignments required to complete the degree,” shares the Pabhoi village resident.

Heirloom seeds are genetically diverse, don’t require chemical-laden fertilisers, and are naturally resistant to disease and pests.

In 2001, he inherited 18 acres of land from his father. Around the same time, he read Rachel Carson’s book ‘Silent Spring’, which highlighted the environmental harm caused by the indiscriminate use of pesticides. Motivated by Carson’s message, Neelam resolved to transition his land into an organic farm. By 2003, he had successfully converted his entire acreage to organic cultivation.

“After switching to organic farming, I found out there were no organic seed varieties available in the market. While some were accessible for rice, none were available for vegetables. The absence of reserves or authenticity in seed sources was concerning. Instead, the market was saturated with genetically modified hybrid seeds. This was a big worrying factor,” he says.

That’s when he also observed that most of the farmers in the Northeast were switching to hybrid seeds and overlooked . “After the Green Revolution, it was clear that only hybrid seeds were to be supplied to the market to the farmers. This was never a solution for an ‘evergreen’ revolution,” he opines.

“While hybrid seeds offer higher yields in one season, they cannot be saved for the following year. Consequently, farmers neglected heirloom seeds, leading to a loss of their sovereignty over time,” he points out. Since then, Neelam’s mission has been to conserve decade-old seeds for future generations.

Backed by the traditional wisdom imparted by his father and the elderly in the village, he set out in search of these heirloom treasures. In the past 15 years, Neelam has conserved nearly 800 varieties of vegetables like tomatoes, chillies, capsicum, basil, and 200 — including madhuri, nanyya rice, sticky gum rice, black rice, soft rice, and joha.

“These seeds have their own identity in terms of taste, colour, and shape. They are adaptable to the diverse Indian climatic zones. In one way, they are more resilient than hybrid seeds,” he says.

Hybrid vs heirloom seeds

Neelam says he wanted the local farmers in his region to wholeheartedly adopt and switch to heirloom seeds.

Explaining the difference between hybrid and heirloom seeds, Neelam says, “While hybrid varieties give more yield, they are produced via genetic manipulation. We compel hybrid seeds to grow using external fertilisers and chemicals.”

“Farmers in Punjab, Western Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Haryana are extremely dependent on these outside inputs,” he adds.

Neelam further points out that, unlike heirloom varieties, the seed saved from hybrids does not grow true to its type in the next cycle. “They will be less vigorous and more genetically variable. If you cannot replicate it, there is no point in keeping the seeds. It only compels farmers to buy new seeds every year,” he says.

“Meanwhile, heirloom seeds are genetically diverse, don’t require chemical-laden fertilisers, and are naturally resistant to disease and pests. As they are open-pollinated, you can easily replicate those seeds next year,” he informs.

Giving an example of how the produce harvested from both varieties differ, Neelam says, “Today, tomatoes are available year-round, unlike in the past when we only had them in winter. To satisfy demand, farmers now grow tomatoes in mountainous areas with heavy fertiliser use. However, organically grown tomatoes in their respective seasons may not last as long but are richer in nutrients, tastier, and more vibrant in colour.”

He continues, “In France, various tomato varieties were once used in different recipes, but now a single, sweeter tomato is used universally, replacing the sour ones of the past.”

Neelam has trained 24,000 farmers across the Northeast.

Neelam says he wanted the local farmers in his region to wholeheartedly adopt and switch to heirloom seeds. “Otherwise there’s no point doing all this work,” he says, adding that his work received a great response from the community.

So, going beyond conserving seeds at an individual level, Neelam now trains thousands of farmers in seed conservation. So far, he has trained 24,000 farmers across the Northeast — including states like Nagaland and Arunachal Pradesh — helping them grow and conserve their own heirloom seeds.

Each year, Neelam sells approximately 8,000 packets of heirloom seeds at Rs 99 each to farmers. With these seeds and the training he provides, farmers can cultivate crops and harvest new seeds for the next cycle, ensuring sustainable food security — a goal Neelam passionately pursues to this day.

For the past 10 years, Diganata Bora has been cultivating vegetables using such heirloom seeds on his two-acre farm in Paschim Manjiri village of Assam.

“Compared to hybrid varieties, we get good yield using heirloom ones. In a bigha [0.33 acre], we now get 6-7 quintals of vegetables over 2-2.5 quintals. Additionally, our input expenses of Rs 40,000 have been reduced to zero as we use readily available cow dung as fertiliser. I am so happy to have decided to switch; now our soil fertility has also improved,” Diganata tells The Better India.

Neelam concludes, “Back when I began , there were no resources available for me to learn from. Now, I’m happy to have created a helpful platform for other farmers. When I visit their fields, I feel great to see the joy on their faces. By cultivating their own organic seeds and crops, they’ve made agriculture economically viable in our region.”

Edited by Pranita Bhat; All photos: Neelam Dutta.