Imagine a world where every child, regardless of their abilities, has the opportunity to play, learn, and grow. Unfortunately, for millions of

, this is not the reality. Often faced with societal barriers and limited opportunities, they struggle to reach their full potential.

However, a spark of hope has ignited in the form of two young visionaries, Siddhant and Suhani. At just 16 years old, these cousins from opposite sides of the globe have united to create ‘INTECH – Technology for Inclusion’, a groundbreaking initiative that is transforming the lives of children with intellectual disabilities.

Growing up in Mumbai, Siddhant was immersed in the world of special education, thanks to his mother’s dedicated work with children with intellectual disabilities. Witnessing their daily challenges firsthand, he was deeply moved to find a way to alleviate their struggles and empower them to reach their full potential.

“When I saw my mother working with children with intellectual disabilities, it really instilled an interest in me to contribute in any way possible,” Siddhant tells The Better India.

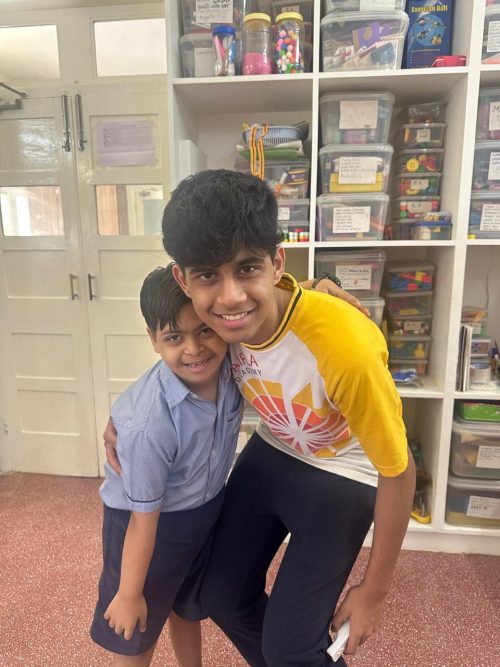

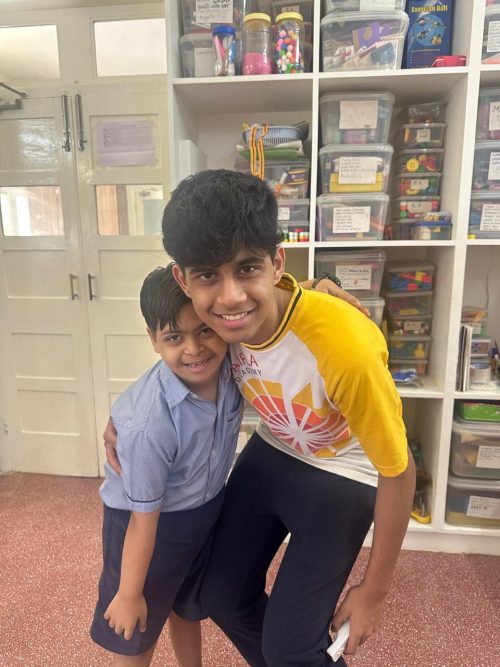

Siddhant supports the children as they play on Nintendo Wii, helping them build confidence.

Siddhant’s understanding of the challenges faced by children with intellectual disabilities was personal and deep-rooted. He was particularly aware of how children with disabilities were often excluded from sports due to mobility limitations and social barriers. Inspired by his mother’s work and driven by his own passion for sports, Siddhant sought a way to confront the challenge.

Across the globe, Suhani, equally driven by a desire to create change, had witnessed the transformative potential of . “In the US, students with intellectual disabilities are integrated into public schools, but in India, this inclusion is often missing,” she says, adding, “Witnessing this disparity has fuelled my passion for change. We recognise the inequality, and we are committed to addressing it, in line with the Sustainable Development Goal 10: Reduced Inequalities.”

Together, they realised they could combine the power of technology and sports to offer children vital skills like communication, motor abilities, and confidence. What began as a spark of inspiration between two cousins soon ignited into INTECH, an initiative to bridge gaps and offer children with intellectual disabilities the chance to thrive and play like never before.

“We wanted to use sports to help develop various skills, but the challenge was figuring out how,” Siddhant explains. After considering different approaches, they stumbled upon an idea that would change everything, the motion-sensing technology.

The breakthrough came when Siddhant recalled his personal experience with a Nintendo Wii — a popular gaming console known for its motion-sensing capabilities. The Wii uses a remote that tracks physical movements, allowing players to engage in sports-like activities like tennis, bowling, and golf without actually stepping onto a field. This interactive gaming experience, where on-screen characters mirror the player’s motions, seemed like an ideal way to engage children who faced physical disability.

“I had a Nintendo Wii at home and thought it could be useful for these children. But I wanted to validate this idea,” Siddhant recalls. To ensure its medical value, they and doctors, who confirmed that motion-sensing technology is already being used in the medical field for physiotherapy.

Shaurya Kuldeep, a child with Down syndrome, takes interest in playing the games on Nintendo Wii.

“The Nintendo Wii games help improve focus, attention, visuomotor perception, strength, and endurance,” Dr Melitta Edward Menezes, a paediatric physical therapist, working with children with developmental disabilities for 12 years, says, recalling how a boy named Sachin, who wore a leg brace, showed increased motivation to stand and engage in physical activity. “The games made it fun for him to participate while also providing the benefits of exercise,” she explains.

Pointing out that the technology provides a unique opportunity for children with intellectual disabilities to virtually swing a tennis racket or bowl a strike, all from the comfort of their own space, Siddhant explains that it takes away any external challenges for such children. “By using the Wii, children who struggle to engage in physical sports can still experience them virtually.”

Implementing this idea came with its own set of challenges. One of the first obstacles was ensuring full participation, particularly for children with severe mobility restrictions caused by . “For one child, it was difficult to even stand up, let alone play a game like tennis,” Siddhant says. To overcome this, Siddhant had to tailor the sessions, often investing extra time to help the children gain the confidence necessary to engage in the activities.

Another challenge was keeping the children engaged for extended periods; many children with intellectual disabilities struggle with focus and attention, making it difficult for them to stay interested in an activity for a prolonged period. “Not all kids can keep focus for a long time, but we tried to make the games enjoyable for them, so they could stay engaged,” Siddhant shares.

Through Nintendo Wii, Shaurya has gained the confidence to play the games on his own.

Over time, through consistent practice and by making the experience interactive, he began to see remarkable improvements in the children’s ability to stay focused. “The key was to ensure the experience was fun and engaging, rather than just a routine task,” he says.

One of the biggest hurdles, however, was teaching the children the rules of the games. At first, the concept of scoring or tracking points was foreign to many. “When I explained to a child that his score was adding up to something bigger, he began to grasp the concept and feel a sense of accomplishment,” Siddhant says. With patience, encouragement, and positive reinforcement, the children gradually began to grasp the rules. As they progressed, they took pride in their newfound understanding, and with each small victory, their confidence grew.

“My brother, Shaurya, was born with . He doesn’t like to go out and play because children his age don’t include him. But with the Nintendo Wii, he can play whenever he wants. It’s made a huge difference in his life,” says Jhanvi Kuldeep, one of many individuals positively impacted by INTECH. “Now, when I take him to places like the mall or timezone to play games, he no longer needs my help,” she adds.

At the Jai Vakeel Foundation, where Siddhant and Suhani first implemented the Nintendo Wii technique, therapists tracked the children’s progress using four key parameters — motor skills, communication, . These were measured both before and after the gaming sessions, with the results showing clear progress.

For instance, one child, who had struggled with mathematics, began to show remarkable improvement during a bowling session. “I asked him to tally up the scores after each round, and he showed interest in doing the mental maths. His therapist later told me that in class, he couldn’t do simple addition. But with the game, he did it without any trouble,” Siddhant says.

The moment was a breakthrough, not only in terms of academic skills but also in how the game was helping to enhance focus and cognitive abilities.

The Wii uses a remote which allows players to engage in sports-like activities without actually stepping onto a field.

Since then, INTECH has expanded to two other schools, Anza Special School and AK Munshi School, both in Mumbai. “By 2025, we aim to be in 50 schools. With 475 disability schools in Maharashtra, our goal is to reach as many as possible by the end of 2026. Our project can last as long as we can make it, and our mission is to keep expanding and make the largest impact we can,” explains Suhani.

Though they live in different countries, Suhani and Siddhant work seamlessly together. Suhani handles the data collection, fundraising, and event organisation, while Siddhant focuses on working directly with the children in India. Suhani admits that managing an initiative from different time zones was a challenge, but they made it work.

“Although we’re continents apart and it may seem like there’s a disconnect, Siddhant sends me videos and pictures, and I hear directly from the students. That helps me feel connected and like I’m truly part of the experience,” Suhani says.

Suhani plays a crucial role in raising funds for the INTECH Inclusion initiative.

Suhani’s network in the US played a crucial role in raising funds for the initiative. “We raised $2,000 through community outreach, social media, and events,” she shares. People were so moved by the project’s mission that many even donated their used Wii consoles. This allowed INTECH to expand, purchasing more devices and reaching additional schools.

Through persistence and research, the two 16-year-olds have been able to break down barriers and create opportunities for children with intellectual disabilities. As they continue to expand their reach, Siddhant and Suhani remain committed to their idea of making the world a more inclusive place.

“Children with intellectual disabilities may face certain limitations, but they also deserve to be included and live a normal life. We want to help them achieve that,” Siddhant asserts.

Edited by Arunava Banerjee; All photos courtesy Deepti Malik Gubbi

However, a spark of hope has ignited in the form of two young visionaries, Siddhant and Suhani. At just 16 years old, these cousins from opposite sides of the globe have united to create ‘INTECH – Technology for Inclusion’, a groundbreaking initiative that is transforming the lives of children with intellectual disabilities.

Growing up in Mumbai, Siddhant was immersed in the world of special education, thanks to his mother’s dedicated work with children with intellectual disabilities. Witnessing their daily challenges firsthand, he was deeply moved to find a way to alleviate their struggles and empower them to reach their full potential.

“When I saw my mother working with children with intellectual disabilities, it really instilled an interest in me to contribute in any way possible,” Siddhant tells The Better India.

Siddhant supports the children as they play on Nintendo Wii, helping them build confidence.

Siddhant’s understanding of the challenges faced by children with intellectual disabilities was personal and deep-rooted. He was particularly aware of how children with disabilities were often excluded from sports due to mobility limitations and social barriers. Inspired by his mother’s work and driven by his own passion for sports, Siddhant sought a way to confront the challenge.

Across the globe, Suhani, equally driven by a desire to create change, had witnessed the transformative potential of . “In the US, students with intellectual disabilities are integrated into public schools, but in India, this inclusion is often missing,” she says, adding, “Witnessing this disparity has fuelled my passion for change. We recognise the inequality, and we are committed to addressing it, in line with the Sustainable Development Goal 10: Reduced Inequalities.”

Together, they realised they could combine the power of technology and sports to offer children vital skills like communication, motor abilities, and confidence. What began as a spark of inspiration between two cousins soon ignited into INTECH, an initiative to bridge gaps and offer children with intellectual disabilities the chance to thrive and play like never before.

Why Nintendo Wii?

“We wanted to use sports to help develop various skills, but the challenge was figuring out how,” Siddhant explains. After considering different approaches, they stumbled upon an idea that would change everything, the motion-sensing technology.

The breakthrough came when Siddhant recalled his personal experience with a Nintendo Wii — a popular gaming console known for its motion-sensing capabilities. The Wii uses a remote that tracks physical movements, allowing players to engage in sports-like activities like tennis, bowling, and golf without actually stepping onto a field. This interactive gaming experience, where on-screen characters mirror the player’s motions, seemed like an ideal way to engage children who faced physical disability.

“I had a Nintendo Wii at home and thought it could be useful for these children. But I wanted to validate this idea,” Siddhant recalls. To ensure its medical value, they and doctors, who confirmed that motion-sensing technology is already being used in the medical field for physiotherapy.

Shaurya Kuldeep, a child with Down syndrome, takes interest in playing the games on Nintendo Wii.

“The Nintendo Wii games help improve focus, attention, visuomotor perception, strength, and endurance,” Dr Melitta Edward Menezes, a paediatric physical therapist, working with children with developmental disabilities for 12 years, says, recalling how a boy named Sachin, who wore a leg brace, showed increased motivation to stand and engage in physical activity. “The games made it fun for him to participate while also providing the benefits of exercise,” she explains.

Pointing out that the technology provides a unique opportunity for children with intellectual disabilities to virtually swing a tennis racket or bowl a strike, all from the comfort of their own space, Siddhant explains that it takes away any external challenges for such children. “By using the Wii, children who struggle to engage in physical sports can still experience them virtually.”

Navigating early roadblocks

Implementing this idea came with its own set of challenges. One of the first obstacles was ensuring full participation, particularly for children with severe mobility restrictions caused by . “For one child, it was difficult to even stand up, let alone play a game like tennis,” Siddhant says. To overcome this, Siddhant had to tailor the sessions, often investing extra time to help the children gain the confidence necessary to engage in the activities.

Another challenge was keeping the children engaged for extended periods; many children with intellectual disabilities struggle with focus and attention, making it difficult for them to stay interested in an activity for a prolonged period. “Not all kids can keep focus for a long time, but we tried to make the games enjoyable for them, so they could stay engaged,” Siddhant shares.

Through Nintendo Wii, Shaurya has gained the confidence to play the games on his own.

Over time, through consistent practice and by making the experience interactive, he began to see remarkable improvements in the children’s ability to stay focused. “The key was to ensure the experience was fun and engaging, rather than just a routine task,” he says.

One of the biggest hurdles, however, was teaching the children the rules of the games. At first, the concept of scoring or tracking points was foreign to many. “When I explained to a child that his score was adding up to something bigger, he began to grasp the concept and feel a sense of accomplishment,” Siddhant says. With patience, encouragement, and positive reinforcement, the children gradually began to grasp the rules. As they progressed, they took pride in their newfound understanding, and with each small victory, their confidence grew.

“My brother, Shaurya, was born with . He doesn’t like to go out and play because children his age don’t include him. But with the Nintendo Wii, he can play whenever he wants. It’s made a huge difference in his life,” says Jhanvi Kuldeep, one of many individuals positively impacted by INTECH. “Now, when I take him to places like the mall or timezone to play games, he no longer needs my help,” she adds.

Tracking progress, expanding reach

At the Jai Vakeel Foundation, where Siddhant and Suhani first implemented the Nintendo Wii technique, therapists tracked the children’s progress using four key parameters — motor skills, communication, . These were measured both before and after the gaming sessions, with the results showing clear progress.

For instance, one child, who had struggled with mathematics, began to show remarkable improvement during a bowling session. “I asked him to tally up the scores after each round, and he showed interest in doing the mental maths. His therapist later told me that in class, he couldn’t do simple addition. But with the game, he did it without any trouble,” Siddhant says.

The moment was a breakthrough, not only in terms of academic skills but also in how the game was helping to enhance focus and cognitive abilities.

The Wii uses a remote which allows players to engage in sports-like activities without actually stepping onto a field.

Since then, INTECH has expanded to two other schools, Anza Special School and AK Munshi School, both in Mumbai. “By 2025, we aim to be in 50 schools. With 475 disability schools in Maharashtra, our goal is to reach as many as possible by the end of 2026. Our project can last as long as we can make it, and our mission is to keep expanding and make the largest impact we can,” explains Suhani.

Working from different timezones

Though they live in different countries, Suhani and Siddhant work seamlessly together. Suhani handles the data collection, fundraising, and event organisation, while Siddhant focuses on working directly with the children in India. Suhani admits that managing an initiative from different time zones was a challenge, but they made it work.

“Although we’re continents apart and it may seem like there’s a disconnect, Siddhant sends me videos and pictures, and I hear directly from the students. That helps me feel connected and like I’m truly part of the experience,” Suhani says.

Suhani plays a crucial role in raising funds for the INTECH Inclusion initiative.

Suhani’s network in the US played a crucial role in raising funds for the initiative. “We raised $2,000 through community outreach, social media, and events,” she shares. People were so moved by the project’s mission that many even donated their used Wii consoles. This allowed INTECH to expand, purchasing more devices and reaching additional schools.

Through persistence and research, the two 16-year-olds have been able to break down barriers and create opportunities for children with intellectual disabilities. As they continue to expand their reach, Siddhant and Suhani remain committed to their idea of making the world a more inclusive place.

“Children with intellectual disabilities may face certain limitations, but they also deserve to be included and live a normal life. We want to help them achieve that,” Siddhant asserts.

Edited by Arunava Banerjee; All photos courtesy Deepti Malik Gubbi